Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

New to investing: the difference in risk between cash, bonds and shares

You don’t need a lot of money to start investing. What’s more important is to start as early as possible. We’ll show you why in this article.

So far in our first-time investor series we’ve explained the types of returns you can get on both saving in cash and investing your money. We also explained how making regular contributions can really work magic over time.

The next step is to consider how you going to afford to put money aside for investing. To illustrate the point, let’s look at two different people and how they might be able to juggle their finances so there is money available each payday to invest.

Sam, an engineering graduate has just secured himself a job at a big engineering firm and one day wants to go to into space. He is ambitious and plans to move up the corporate ladder but he is also keen to secure his financial security and starts contributing to his pension straight away. He can afford to invest £1,000 a year which works out at just over £83 a month.

Julie is at catering college and hopes to fulfil her dreams by following in the footsteps of her mother and becoming a Michelin-starred chef. She is living at home and can afford to save £40 a month but decides that is too small to make a difference. ‘I will start saving seriously when I get a well-paid job,’ she says.

She decides to wait and 10 years later tries to make up for lost time by putting aside £2,000 a year.

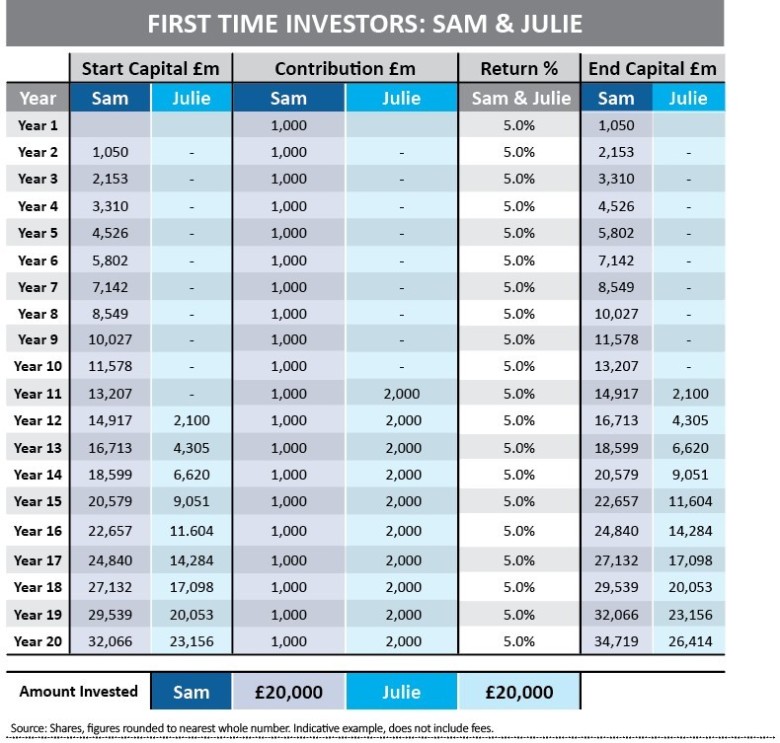

The accompanying table shows how much they’ve both invested and made over 20 years. To be conservative we have assumed that both Sam and Julie achieve annual growth in their investments of 5% a year, below the long-term average return of 7.3% a year for UK stocks and shares. This is for illustrative purposes only. Actual returns will be much more variable and sometimes negative.

The first thing that jumps out from the tables is that Sam’s investment pot is 31% bigger than Julie’s, giving him an extra £8,305. Notice that both invested the same £20,000. This demonstrates the power of compounding as we discussed in our first article.

If Sam had aimed to make the same amount as Julie (£26,414) he could have reduced his annual contributions to around £760, giving him more disposable income.

We can’t emphasise this enough – starting early, even if in a small way, is much more effective and cheaper than waiting until you are older and perhaps earning more.

WOULD YOU PREFER BUNGEE JUMPING OR A CUP OF COCOA?

Investing is not about putting your money into any stock or fund in the hope of getting the best returns. You need to pick your investments wisely and also consider how you might feel about losing money if some investments go wrong.

If you can’t bear the thought of losing a chunk of your money, it might suggest that you don’t have a large appetite for risk. Therefore you would need to consider only investing in lower-risk assets which might mean you don’t reach your financial goals or you perhaps need to increase your future investment contributions.

It all comes down to making a plan that suits your temperament and lifestyle while giving you the best chance of staying the course and not panicking or swerving off course.

Read on and we’ll give you some examples of higher and lower risk investments.

It’s worth thinking about different investment types as being rungs on a ladder. At the bottom end of the ladder is the lowest risk investment. The risks increase as you climb the ladder. Shares are near the top.

The position of funds on the risk ladder depends on what’s inside their portfolio. An ‘equity’ fund will contain shares and potentially a very small allocation to cash or bonds. A multi-asset fund will have a mixture of shares, bonds and cash and potentially some commodities and property exposure.

HIGHER RISK

Investing all your money in shares is considered an ‘aggressive’ stance and is only suitable for younger people who have a very long investment horizon. It also requires a strong stomach and the fortitude to handle tough times when the value of your portfolio falls.

Although the long-term return from UK shares has averaged 7.3% a year, along the way there have been some prolonged periods of negative returns. These are often called bear markets and on average they have lasted 14 months and delivered negative returns of 33%.

Counter-intuitive as it may sound, the stock market would need rise by 50% to recover losses of 33%, which means if you invested near the prior peak, your portfolio could be ‘under water’ for an extended time. This is why it is advisable to invest for a minimum of five years and preferably longer.

If you are the type to get anxious and lose sleep after reading about coronavirus headlines hitting the value of your investments, you might be better off with a portfolio that moves around less and is more stable.

LOW (OR NO) RISK

The easiest way to achieve more stable returns is to stay in cash. Cash deposits at UK banks are protected up to £85,000 per institution by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, so effectively any cash you hold this way is guaranteed.

However, the downside is the low interest rates on offer, which are often below the rate of inflation, which means that the purchasing power of your cash falls over time. It’s unlikely that a saving pots entirely in cash will meet your long-term financial goals.

MEDIUM RISK

Another way of reducing variability but getting a better return than cash is to put some money into fixed interest investments, sometimes called bonds. This type of investment has historically returned more than cash but less than shares.

A bond is like an ‘IOU’ – a government or company borrows money from an investor by issuing bonds in exchange for cash. They then pay a fixed amount of interest over a specific time period; at maturity the investor cashes in the bond for its original face value

(also known as ‘par’).

You often see people discuss bonds in terms of their yields. This can be confusing given that stocks are discussed in terms of share prices. You just need to understand that bond yields move in the opposite direction to the price. So when someone says a bond’s yield is falling, the price is actually rising.

Bonds are also good to put into a portfolio because historically they tend to do well when equities fall, because they are considered safer. Also the Bank of England tends to reduce interest rates during economic contractions, which increases bond prices. Having some bonds in your portfolio therefore adds some stability.

GETTING THE RIGHT MIX FOR YOU

For most people, having a mix of stocks, bonds and cash is a sensible way to invest for the long-term.

The precise mix will always depend on your individual financial circumstances, age and temperament, but the principles laid out here should help you create a useful framework.

We’ll look at asset allocation – another term to describe the mix of stuff in your portfolio – in more detail later on in this education series.

HOW MUCH DO I NEED TO INVEST?

Now you’ve got an idea about the different levels of risk attached to cash, bonds and shares, it’s time to think about some goals, i.e. how much would you like to make from investing or think you will need at a certain point in the future?

People are notoriously bad at thinking about how they will feel about some event a long way into the future, but it pays to give it serious consideration. The calculation is made doubly-hard by the fact

that we need to adjust numbers for inflation.

For example, your council tax goes up every year due to the effects of inflation and therefore you need to factor this increase into your future spending needs.

To illustrate, let’s say inflation averages 2% for the next 30 years. After 30 years your £2,000 annual council tax bill will be 81% higher at £3,622.

In the same way, if you had targeted living off a pension generating £30,000 a year in 30 years’ time, that is equivalent to £54,340 in today’s money.

Don’t forget your state pension which currently pays £8,767 a year and fortunately it will rise by 2.5%, the rate of inflation or average earnings growth, whichever is largest. If we assume 2.5% annual increase, the state pension should pay out £15,880 a year in 30 years’ time.

If we reduce our pension pot return target by the assumed inflation-adjusted state pension figure (£54,340-£15,880), we arrive at a target annual income goal of £38,460 in real inflation-adjusted terms.

THINK ABOUT LONGEVITY

We can now figure out the size of the investment pot needed to generate the desired level of annual income. But for how long do we need this income? As morbid as it sounds, we first we need to estimate life expectancy.

According to the Office for National Statistics, a 30-year-old woman is expected to live for 84 years and a man for 80 years. The future retirement age will probably creep higher as pressures on the pension system build from an ageing population. Assuming that both sexes retire at 67, the pension would need to last from between 13 and 17 years.

Nobody wants to run out of money, so to be cautious we have assumed that a 30-year-old today will need to fund 24 years of income in retirement. Even this might not be conservative enough.

To fund the annual spend of £38,460 and not run out of cash for 24 years would require an investment pot of £572,000. To reach this target requires a monthly investment of £683. That may be beyond a lot of people’s means so just save as much as you can.

A rough rule of thumb for estimating the size of pension pot you need is to multiply your required annual income by 15.

Expending a little effort to make a financial plan suited to your circumstances and risk appetite can pay off over the long haul.

NEXT TIME IN OUR FIRST-TIME INVESTOR SERIES

– Should I run my own investment account or get someone else to do it?

– Choosing an ISA or SIPP provider

– How to open an account and make an investment

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine