Beware the bear (steepener)

One of the most intriguing facets of financial markets of the past two years has been the differing messages offered by bond yields and share prices.

The bond market, via the so-called inverted yield curve, has been predicting a recession. The stock market has instead priced in a cooling in inflation, a gentle economic landing and a pivot to interest rate cuts from central banks, with the result that headline equity indices from America to Australia, France to Taiwan and Canada to Germany have set new all-time highs.

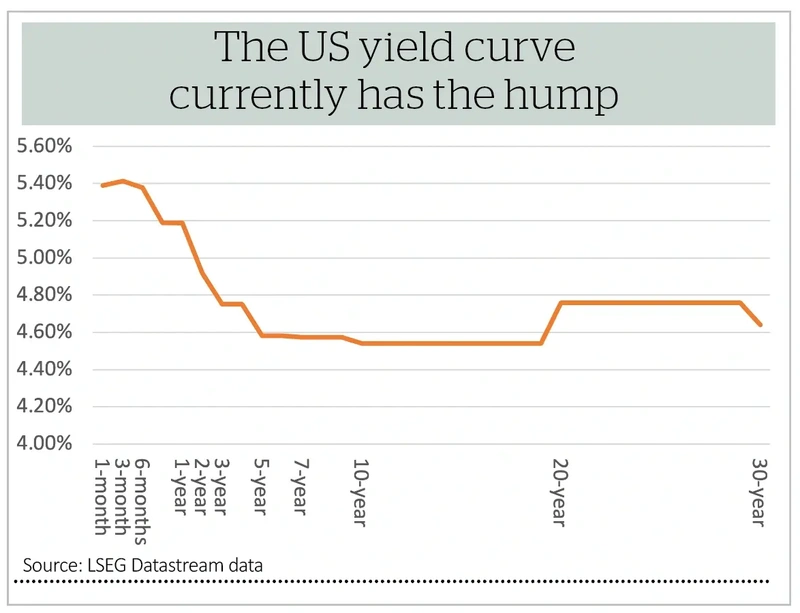

Usually, the yields on long-term bonds are higher than those on short-term paper. This is simply because lenders (or bond buyers) demand a higher return to compensate them for the increased risk of something going wrong during the additional time such as changes in interest rates, higher inflation or, at worst, a default by the issuer (or borrower).

The usual shape of the yield curve therefore goes from the bottom left of the screen to the top right, in a gently steepening path.

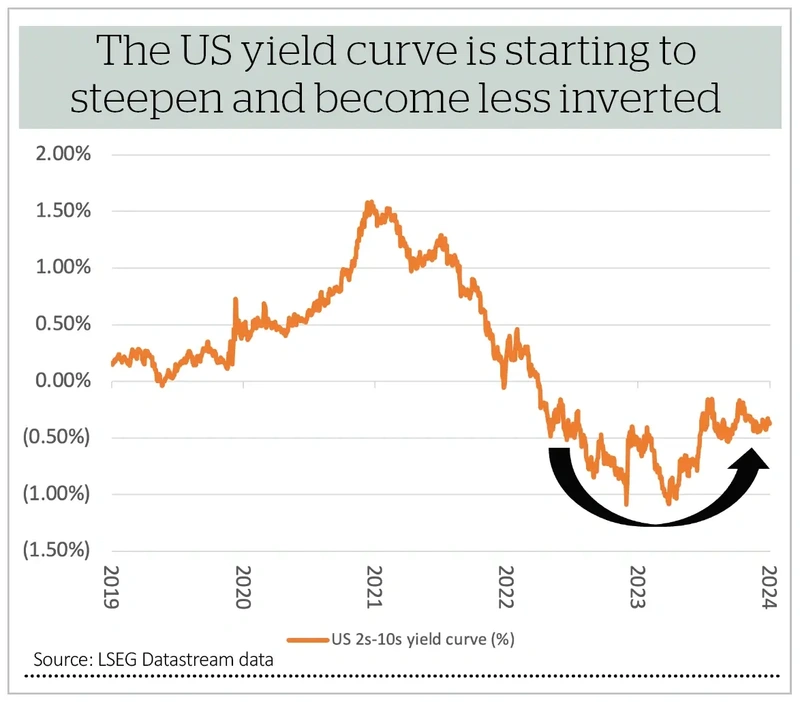

An inverted curve means long-term rates are lower than short-term ones. This means markets think that interest rate cuts are coming in response to a slowdown or recession. A shorthand version of this can be provided by comparing just the yield on two- and 10-year government bonds.

FOUR OPTIONS

The yield curve changes shape according to variations in the yield on each individual maturity, as it flattens or steepens, and there are four possible scenarios here:

- A bull flattener, when long-term yields (and interest rates) fall faster than short-term ones, so the yield spread shrinks. This is usually how markets discount interest rate cuts and can be seen as positive for bond prices (as yields fall) and share prices (as a recovery in profits, dividends and cash flow is anticipated). The longer the duration the more favourable it is, and this can include assets such as long-dated bonds and equity sectors with a big chunk of their earnings in the future, like technology and biotechnology.

- A bear flattener, when short-term yields rise faster than long-term ones, so the difference between the two again narrows. This is usually seen as a harbinger of recession, or at least interest-rate hikes and tighter monetary policy, and is thus potentially negative for share prices, especially for areas like banks and cyclicals.

- A bull steepener, when short-term yields fall faster than longer-term ones, so the spread, or differential between them widens. This is usually seen when markets are pricing in interest-rate cuts and is thus bullish for bonds and equities.

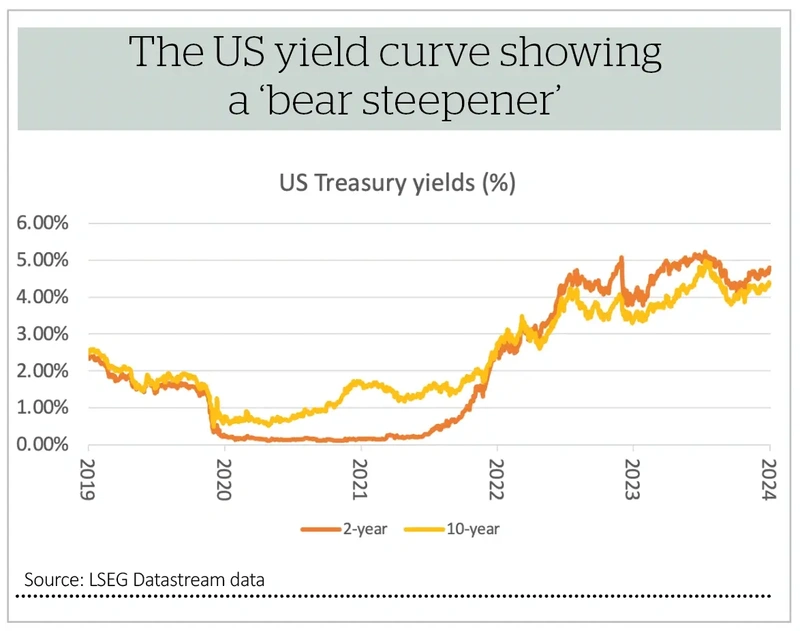

- A bear steepener, when both short- and long-term yields are rising but long-term ones are rising faster to widen the gap between the two. This can be bad news for bonds in particular, as prices fall when yields rise, and it can be a sign inflation is on the rise. It could be a challenge for share prices, too, as it combines higher discount rates (that lower the theoretical value of the long-term cash flows of long duration sectors like tech and biotech) with tighter monetary policy that hits the earnings power of short-duration, cyclical industries.

Right now, we have a bear steepener on our hands in the US.

FOLLOW THE BEAR

If the US economy slows down there could be trouble ahead for equities, but given the amount of fiscal stimulus being applied that does not seem so likely for now almost irrespective of who wins the US presidential election in November.

The issue at hand could therefore be inflation instead, especially as the Biden administration is on course to add $7 trillion to America’s national debt during its four-year term (and the total deficit only reached that level for the first time in 2003).

That does not mean it is game over for the stock market’s bull run. It could mean a more difficult environment for bonds and yield-offering bond proxy stocks like utilities and consumer staples, or it could mean a more difficult environment for long-duration sectors like tech and biotech.

It could also mean a more interesting environment for companies with pricing power and for commodities, if investors repeat the 1970s’ strategy of looking toward ‘hard assets’ as a store of value relative to paper ones, such as cash and bonds, the real value of which may be eroded by the ravages of inflation.

Or the bond market could just be flat out wrong. It has wrongly been predicting a recession. It is now predicting inflation. But the signals emanating from bonds still do not sit easily with the equity markets’ preferred narrative of cooling inflation, slow growth and interest rate cuts. Someone is going to be wrong somewhere.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Danni Hewson

Feature

Great Ideas

News

- Lloyds Bank cuts risk monitoring in effort to drive change

- Lok’n Store shares leap on Shurgard cash offer

- Shares in personal care firm PZ Cussons hit 20-year low

- Has Associated British Foods-owned Primark maintained its momentum?

- Prospects for US interest rate cuts reduced as inflation remains sticky

- Service sector inflation undermines market rally

- Can Amazon continue to beat ‘The Street’?

- What have we learned from the US banks’ first-quarter updates?

magazine

magazine