Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

“Even a war in the Middle East is not persuading investors to buy US Treasuries, or government bonds, an asset class that is usually seen as the ultimate haven because they are priced in the world’s reserve currency and come with the backing of America, the world’s leading economic and military power,” says AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould.

“There are three possible trends behind the ongoing increase in the benchmark ten-year Treasury yield (and thus the ongoing fall in its price) and three reasons why it matters so much – and investors must watch them all very, very closely.

“The yield on the US ten-year Treasury bottomed more than three years ago but the rate of increase has accelerated and become much more pronounced in 2023.

Source: Refinitiv data

“There are three possible explanations for why investors are demanding a higher yield from the US ten-year to compensate themselves for the possible risks attached with owning the paper and lending money to Americans at a fixed coupon for a fixed period of time:

It is not certain that inflation is cooling. The US headline rate is 3.7% as of September, unchanged from August and above not just the 3% trough seen in June but the Fed’s 2% target. Oil prices had already risen sharply before the latest round of conflict between Hamas and Israel and if crude prices go, and stay, higher, that could make it harder to rein in inflation.

In response to this sticky inflation, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell is asserting that interest rates could stay higher for longer to ensure that inflation is beaten back toward the US central bank’s 2% target. Markets are pricing in more than one more Fed rate hike, but the first cut is not expected until summer 2024 at the earliest – a massive change from this time a year ago, when the rate cutting cycle was expected to have begun by now.

US Federal debt continues to mushroom. Government borrowing has increased by $1.6 trillion since April’s debt deal, to take the total to $33 trillion. The rate of increase, fuelled by higher spending and sagging tax income, means that the US will need to sell more Treasuries to fund its debts. Worse, America needs to refinance around $15 to $17 trillion of its existing debt in the next two years. Worse still, the US Federal Reserve is no longer acting as the price-blind buyer of last resort, since it has ended its Quantitative Easing (QE) bond-buying scheme and started to run a Quantitative Tightening (QT) programme, whereby it does not reinvest the proceeds as bond holdings mature.

“This is a painful combination. Any signs of these trends going into reverse could therefore put a lid on the benchmark ten-year yield, and, at some stage, investors will presumably decide yields have reached such a level that they are just too tempting to ignore, as they more than compensate for the evident risks on offer.

“However, we do not seem to be there quite yet and the future trend in the US ten-year yield matters for three reasons, especially bearing in mind that the US ten-year yield bottomed at 0.51% in August 2020. Since then, the US ten-year bond index has fallen by 31% (since yields and prices have the same inverse relationship for bonds as they do for equities) and the decline in the ten-year bond index from early 2020’s peak has wiped out all of the gains made by that price benchmark since November 2008.

Source: Refinitiv data

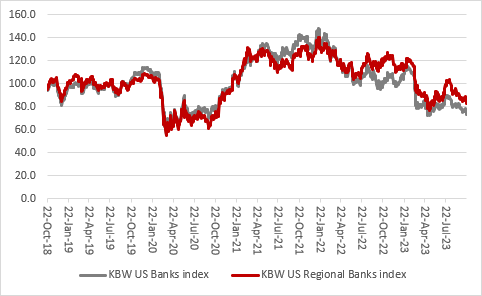

The US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) reports that, as of the end of June, American banks are sat on $311 billion of unrealised losses on held-to-maturity securities. The good news is accounting rules mean they do no longer have to mark-to-market and book those losses each quarter. The bad is that any unexpected run on deposits could force banks to liquidate to raise cash, thus crystallising those losses (rather as happened at Silicon Valley Bank in the spring). If the banks can hold the securities – which include a lot of US Treasuries – until maturity, then all may be well, but these potential losses are sitting in plain sight and so are the risks. The share prices of US banks are paying attention to the dangers.

Source: Refinitiv data

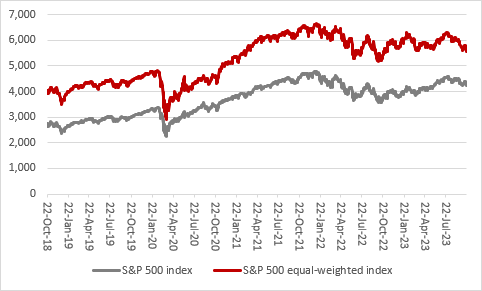

The US ten-year is the risk-free rate against which returns from all other assets are judged and the benchmark against which the cost of all other loans is judged. The US will not default, and it will pay the coupons. Any other investment (or loan) must provide a higher return to compensate for the additional risks. The easiest way to get a higher return is to pay a lower price, so rising yields could yet weigh on valuations elsewhere. While the S&P 500 equity index is up 10% this year, the equal-weighted version of the benchmark (which irons out the impact of the Magnificent Seven megacaps of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, NVIDIA, Microsoft and Tesla) is down 3%. More tellingly, even with the help of the Magnificent Seven, the S&P 500 has yet to recapture its 2021 high.

Source: Refinitiv data

America’s huge debts mean it cannot afford a sustained increase in their cost. The US government’s annualised interest bill is running at $1 trillion, when total tax income is only $5 trillion (and that is when the economy is doing well), while a modest slowdown in debt growth in 2007-09 resulted in near disaster. These numbers speak against rates staying higher for longer and a quick look at the history of the Fed Funds rate also suggests it is unlikely.

Source: US Federal Reserve, Refinitiv data

“It is not just the government that will be feeling the pips squeak. US 30-year mortgage rates stand at their highest level since 2000, also thanks to the ongoing surge in US Treasury yields, and that is likely to take a toll on the housing market – existing homes sales already languish at a 13-year low, and the Mortgage Bankers Association says volume demand is back to levels last seen in 1995.

Source: FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve

“That suggests rates may come down quicker than markets currently think. It is tempting to view that as good for equities (as lower yields will reduce the relative attractions of cash and bonds). But perhaps markets need to be careful what they wish for.

“First, the Fed’s credibility could be seriously compromised were it to cut rates (or even return to Quantitative Easing) when inflation was still running above target. It would need a pretext for such action, for instance a recession, war (and calls for cheaper funding for the conflict) or ructions in the financial markets.

“Second, the Fed’s history suggests it will cut, but only once something is already broken and the markets or the economy can take no more. Even then, lower Fed rates did little to support falling share prices during the 2000-03 and 2007-09 bear markets as earnings downgrades outweighed and outpaced lower rates and it took a good couple of years for share prices to regain their balance.”

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Wed, 24/04/2024 - 10:37

- Thu, 18/04/2024 - 12:13

- Thu, 11/04/2024 - 15:01

- Wed, 03/04/2024 - 10:06

- Tue, 26/03/2024 - 16:05