Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

“There are few assets as likely to make a mug of investors (as well as central bankers and policymakers) as oil. Crude is relatively price inelastic – demand does not seem to change much regardless of price – but the cost of a barrel still swings all over the place, thanks to the complex dynamics of supply, geopolitics and also the influence of OPEC, the cartel which still tries to use its control over one-third of global output to bend oil prices to its will,” says AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould.

“Oil prices have shed 5% already in 2023, back to barely $80 a barrel after a sharp rally from December’s lows, to leave consumers, politicians and central bankers hoping the slide continues, given the knock-on effects upon inflation and boost to their spending power, but analysts and traders divided over whether black gold will shine in 2023 or not.

Source: Refinitiv data

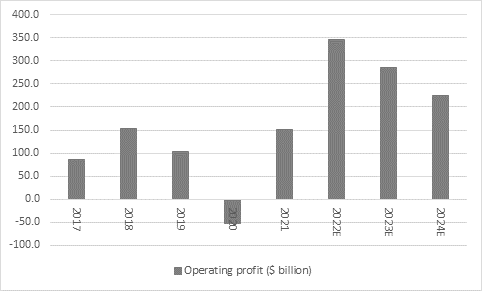

“For the moment, analysts seem inclined to believe that oil (and gas) prices are going to fall in 2023 and 2024, because they are forecasting a one-third fall in operating profit from the West’s seven oil majors between 2022 and 2024, equivalent to a drop of $120 billion (and that is before any change in interest bills or taxes).”

Source: Company accounts, Marketscreener, consensus analysts’ forecasts in aggregate for BP, Shell, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, ENI and TotalEnergies

The case for lower oil in 2023

1. Recession

The International Monetary Fund continues to bang out its drumbeat of doom for 2023, as managing director Kristalina Georgieva warns one-third of the globe could be in recession this year. The IMF’s estimate for 2.7% global GDP growth is the lowest since 2000, excluding the 2007-09 Great Financial Crisis and the 2020 pandemic, and history shows it doesn’t make much of a drop in oil consumption to hit the price hard, given how delicate the balance between supply and demand tends to be. Crude prices plunged in 1980, 1991, 2001, 2008 and 2020 as recession hit home and a slowdown or downturn in 2023 could see a repeat. Oil traders seemed to fear as much in the second half of 2022.

Source: Refinitiv data

2. Geopolitics

In The Art of War, Sun-Tzu asserted that, “No country has ever benefited from a protracted war,” and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is hardly going to plan, almost a year after the initial assault. A peaceful solution and a Russian withdrawal – prompted either by international sanctions or internal pressure – could help oil supply, or at least take the pressure of some key pipelines. Such a scenario seems unlikely at the moment and sanctions against Russian supply could be maintained even if there is a diplomatic solution to the military conflict, but sentiment could be helped if one geopolitical factor were to be taken out of the oil price equation. The EU’s attempt to impose price caps on Russian supply and sanction any insurers who insure vessels that are carrying Russian product by sea could in theory weigh on prices too, even if the $60 cap is a small premium to where the Urals price benchmark currently trades ($54 a barrel).

3. European storage levels and the dash for LNG

The EU has done an amazing job to boost its winter storage levels of liquefied natural gas via the construction of new pipelines and port facilities, including floating storage regasification units (FSRUs), to accommodate a flotilla of ships bearing liquefied natural gas (LNG). The Dutch TTF natural gas price has retreated to pre-invasion levels and the EU’s improved energy supply – coupled with a mild winter, thus far – could take the pressure off demand for other sources of energy, including oil.

4. The long-term trend toward renewables

OPEC’s World Oil Outlook document from 2022 forecasts that renewables (mainly wind and solar) will be the fastest growing source of energy supply between now and 2045, with gas playing a much bigger role, nuclear, hydro and biomass chipping in, oil coming in broadly flat and coal going into steep decline. If even OPEC is forecasting this, bears of oil will argue then there must be a real danger that oil fields become stranded assets as other sources of energy come to the fore.

| Barrels of oil equivalent (million) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | 2021 | 2025E | 2030E | 2040E | 2045E |

| Oil | 88.3 | 96.1 | 98.9 | 100.5 | 100.6 |

| Coal | 74.7 | 74 | 70.7 | 62.1 | 58.2 |

| Gas | 66.4 | 69.9 | 74.9 | 83 | 85.3 |

| Nuclear | 15.2 | 16.3 | 17.8 | 21.7 | 23.3 |

| Hydro | 7.5 | 8 | 8.7 | 10.1 | 10.4 |

| Biomass | 26.2 | 27.9 | 30 | 33.7 | 34.9 |

| Renewables | 7.4 | 11.2 | 17.8 | 32.5 | 38.3 |

| Total | 285.7 | 303.4 | 318.9 | 343.6 | 351 |

Source: OPEC World Oil Outlook 2022

The case for higher oil in 2023

1. China opening up

China is the world’s second-biggest economy and a net importer of oil to the tune of ten million barrels a day or more. The pandemic and lockdowns have constrained demand for the thick end of three years so if the Middle Kingdom can finally shake off covid then there is a chance that oil demand will increase. OPEC is forecasting an average increase in demand of 700,000 barrels a day from China and, alongside higher consumption in India, Latin America and the Middle East, this underpins the cartel’s estimate that global demand will rise by some 2.7 million barrels a day in 2023 to an average of 103 million – a new all-time high. Growth may flatten off a little from there, as other energy sources are given precedence, but oil demand still seems to be growing for now even if the long-term shift away from hydrocarbon consumption seems clear.

| OPEC medium-term oil demand forecasts, Reference Case (millions of barrels per day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022E | 2023E | 2024E | 2025E | 2026E | 2027E | |

| OECD | 44.8 | 46.6 | 47.2 | 47.2 | 47 | 46.6 | 46.2 |

| China | 14.9 | 15.3 | 16 | 16.4 | 16.6 | 16.8 | 16.9 |

| Other non-OECD | 37.3 | 38.4 | 39.8 | 40.9 | 41.9 | 42.8 | 43.8 |

| Total | 96.9 | 100.3 | 103 | 104.4 | 105.5 | 106.3 | 106.9 |

Source: OPEC World Oil Outlook 2022

2. Replenishment of America’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve

If China’s reopening could be one source of incremental demand, America’s need to replenish its Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) could be another. To try and put a lid on oil prices (and presumably curry favour ahead of November’s mid-term elections with voters whose spending power had been hit by higher prices at the gasoline pump), the USA has taken its SPR down to 375 million barrels, according to the latest weekly report from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). That is way below the maximum capacity of 714 million and a figure last seen in December 1983.

Regular reserves are almost unchanged on a year ago, at 419 million barrels, but that figure had swollen to 541 million barrels in early 2020 when covid-19 hit and lockdowns ground the economy (and oil demand) to a halt. Sharp drops in regular stockpiles could boost US demand in future, especially as the Biden administration seems dead set against further drilling on environmental grounds, and at some stage America will surely want to replenish its SPR to buttress its national energy security.

Source: US Energy Information Administration

3. Geopolitics

Sanctions or price caps on Russia, Iran and Venezuela, as well as ongoing instability in OPEC member Libya, could all constrain supply at a time when demand for oil is still growing, especially if China does bounce back and the US does refill at least some if its SPR. OPEC estimates that Russian output could also fall by 850,000 barrels a day in 2023, to around 10 million, as sanctions on parts and Western services expertise hit home.

OPEC also seems keen to manage its output so that oil prices are well underpinned and production cuts remain a key tool in the cartel’s armoury. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq all trimmed production in November, according to OPEC data, even as Nigeria and Angola achieved increases as they responded to fresh weakness in the price of crude.

4. Low levels of investment in supply

One reason that President Joe Biden, and other Western politicians, received seemingly little change when they called on Saudi Arabia and OPEC to increase output and depress oil prices was the West’s ongoing campaign to limit its own hydrocarbon output (and new license issuance) on the (perfectly good) grounds of environmental awareness. To hold back your own supply with one hand and call on someone else to do the dirty work with the other may have looked pretty odd in Riyadh, especially as America spent most of 2016 calling on the Saudis to produce less oil, when the OPEC power ramped production and sought (with a fair degree of success) to puncture the boom in American shale production and maintain its grip on the market.

Politicians and the public continue to beseech oil producers not to explore and drill, while banks are declining to finance new projects, insurers are reluctant to insure them and pension fund managers are reticent about holding oil stocks at best and in some cases actively divesting them. Given this clarion call not to invest in hydrocarbon supply, oil majors are taking heed for fear of reputational damage, regulatory attention, windfall taxes or a combination of all three. As a result, capital investment budgets remain restrained, especially given where oil prices and profits got to in 2022, and output looks unlikely to grow rapidly. This could help to keep the supply-demand balance tight and thus prone to any unexpected demand shocks to the upside (or indeed the downside).

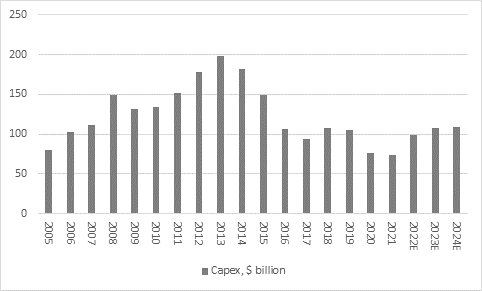

The recognised oil majors – BP, Shell, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, ENI and TotalEnergies – are forecast by analysts to increase capital investment by 8% in 2023 to $107 billion and then again by a fraction in 2024 to $109 billion, and those come after a one-third hike in 2022.

Source: Company accounts, Marketscreener, consensus analysts’ forecasts in aggregate for BP, Shell, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, ENI and TotalEnergies

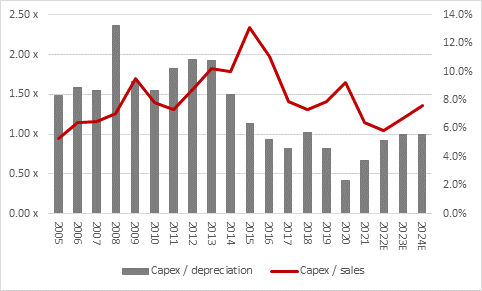

However, those figures include investment in renewables and alternative energy sources. They also leave the aggregate capex budget at barely half of the 2013 peak in dollar terms; at just one times depreciation compared to the 2013 high of nearly two times; and the capex/sales ratio at just 7.6% by 2024, again a long way below the 2015 zenith of 13%. If oil demand does surprise on the upside in any way, these numbers could provide support to crude prices, as it may not be easy to quickly accommodate the increase.

Source: Company accounts, Marketscreener, consensus analysts’ forecasts in aggregate for BP, Shell, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, ENI and TotalEnergies

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Wed, 24/04/2024 - 10:37

- Thu, 18/04/2024 - 12:13

- Thu, 11/04/2024 - 15:01

- Wed, 03/04/2024 - 10:06

- Tue, 26/03/2024 - 16:05