Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

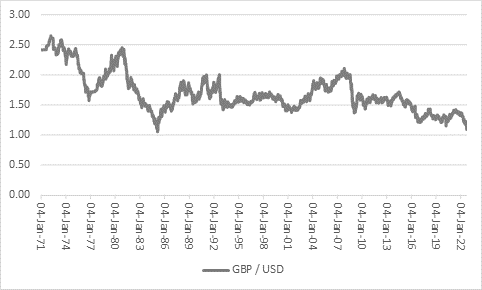

“The pound is trading down around 1985’s all-time bottom against the dollar of $1.05 and multi-year lows in not just sterling but the yen and euro against the greenback also hark back to the mid-eighties when only multi-lateral Government intervention stopped the dollar in its tracks, with the so-called Plaza Accord,” says AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould.

“The G5 – as they were then – agreed at a meeting in New York to devalue the dollar against the Japanese yen, German deutschmark, French franc and the pound, and with the Bank of Japan already intervening in the foreign exchange markets it will be interesting to see if we get any co-ordinated action this time around.

“After that intervention the pound roared back against the dollar to reach $1.50 within six months and almost $2.00 by the end of the decade.

Source: Refinitiv data

“However, it should be noted that the dollar – as benchmarked by the trade-weighted DXY, or ‘Dixie’, index is nowhere near its 1985 zenith of 165 as it currently trades around 113. The Plaza Accord did work, though, as DXY had plunged to around 105 within a year.

Source: Refinitiv data

“Whether central banks feel the need to intervene now in a concerted manner, as they did in 1985 (and again after the G20 meeting in Shanghai in 2016), remains to be seen but the world does not need a strong dollar.

“This is because a strong buck is traditionally seen as deflationary – it increases both the costs of (dollar-priced) commodities and the interest costs of those nations who borrow in dollars and not their own currency, a particular facet of emerging markets. Increased raw material costs eat into corporate profit margins and cash flows (and potentially dividends) while coupon payments to bondholders crimp Governments’ scope to invest and potentially also economic growth.

“We can already see signs of strain.

“Emerging market equities (and bond markets and currencies) are wobbling in many cases, with Sri Lanka, Lebanon and Zambia already wrestling with default and Ghana, Pakistan and Tunisia in trouble.

Source: Refinitiv data

“In addition, commodity prices are weakening, at least according to the basket of raw materials represented by the Bloomberg Commodities index.

Source: Refinitiv data

“Some investors could be forgiven for thinking that a little dollar-strength-inspired disinflation is a good thing, at a time when markets are terrified of inflation and rising interest rates.

“But markets are also fretting about the threat of a recession and dollar strength and disinflation could tip the world over the edge in that direction.

“In this respect, sterling weakness is partly a function of global stresses and strains as well as domestic ones.

“On the home front, the combination of a trade deficit and a budget deficit – to which the new Government is adding – leaves Britain increasingly reliant on overseas funding and what former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney called the ‘kindness of strangers.’ If overseas lenders lose faith in sterling-denominated assets then there could be trouble ahead, especially as a similar combination of an energy crisis, galloping inflation, a current account deficit, a trade deficit and a plunging pound obliged the Labour government of James Callaghan and Denis Healey to call in the International Monetary Fund for a loan in 1976 to help support the value of sterling.

“It feels like it is overdoing it to hark back to such dark days and the pound could easily self-correct, without the need for Government or central bank intervention, co-ordinated or otherwise.

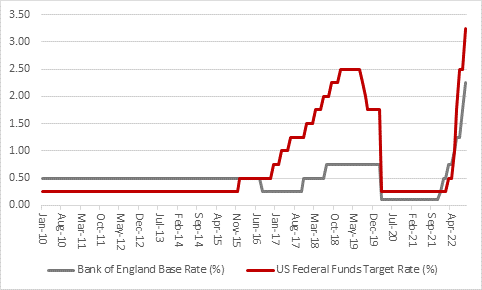

“A further reason for the pound’s weakness against the dollar is the interest rate differential between the US and UK. Right now, the US Federal Reserve Fed funds rate is 3.25% and the Bank of England base rate is 2.25% so markets will be naturally tempted to park their cash in dollars to benefit from the higher interest rate (plus the dollar is now the world’s reserve currency, so it has an added sheen as a haven asset at a time of wider market and economic uncertainty).

“This gap could correct itself. A weak pound could boost British exports, help GDP growth and oblige the Bank of England to raise interest rates, especially if sterling’s slide fuels inflation. At the same time, the strong dollar could weigh on US exports, slow US growth, crimp US inflation and prompt the Fed to cut rates. That would close the interest rate differential and make the pound more attractive on a relative basis, especially as a weak currency could also attract buyers to British assets. We may even already be seeing this looking at the overseas bids for quoted UK firms such as AVEVA, MicroFocus and GB Group, as well as stake building in Vodafone and BT.

Source: Refinitiv data

“But like many football teams, that theory could look good on paper but prove no good in practice as there are many other factors at work.

“In theory, sterling should be attractive because the UK offers rule of law, an independent central bank, a powerful financial ecosystem centred around the City of London, the world’s business language and a plum global time zone which means it is perfectly placed for between financial trading in Asia, Europe and the USA.

“Any erosion of these attractions must therefore be watched. Britain’s ongoing relations with the EU and threats to rip up the Northern Ireland protocol could jeopardise faith in rule of law and any reassessment of Bank of England independence would not be helpful either. At least the Chancellor was quick to reassure here in his fiscal event speech on Friday but there remains the nagging doubt that Brexit will chip away at the City’s predominance, even if the mini-Budget is seeking to address that, too.”

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Wed, 01/05/2024 - 18:32

- Wed, 24/04/2024 - 10:37

- Thu, 18/04/2024 - 12:13

- Thu, 11/04/2024 - 15:01

- Wed, 03/04/2024 - 10:06