Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

“Silvergate, Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank have failed, First Republic Bank has suffered a run leading to liquidity support from other lenders and Credit Suisse has fallen into the arms of bitter rival UBS. Investors could be forgiven for thinking what is coming next, as bank share prices slide and regulators and central bankers alike continue to assert that there is enough liquidity out there, only for them to offer more (and more) of it as it seemingly disappears,” says AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould.

“Ultimately, central bankers and policymakers need to bolster faith by stopping runs on deposits, boosting asset prices (especially for the government bonds owned by banks) and get credit flowing again so that the banking crisis does not spill over into the real economy and provoke a deep recession.

“How? We have been here before, in 2007-09 worldwide and then in the EU during the 2010s when interest rate cuts and Quantitative Easing were the main tools and, perhaps, we are due for a repeat performance.

“That may not sound like a pleasant prospect for central bankers in the UK, EU and USA when inflation is still running above their 2% inflation targets, and they are busy proving their inflation-busting credentials with rate hikes and Quantitative Tightening policies designed to withdraw some of the hot money and stimulus they have pumped into the system since 2008.

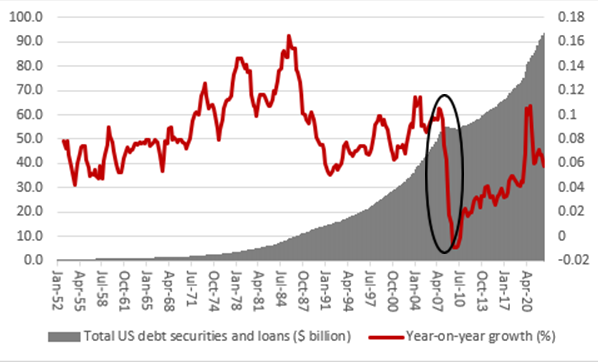

“But the world is now so much more indebted in 2023 than it was in 2009 that a credit shock simply cannot be afforded. A tiny blip in credit growth in the USA in 2008 – the only time credit shrank since 1950 – produced an economic downturn and financial market meltdown of epic proportion.

Source: FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve

“The danger posed by the current loss of confidence in banks is that depositors continue to withdraw their money. This limits banks’ ability to lend and, in extremes, forces them to sell assets to meet withdrawals. That hits asset prices and valuations and further limits lending capacity. In addition, chief risk officers may insist on a tightening of lending standards to reassure depositors but further hitting credit availability.

“For a global economy reliant upon ever increasing amounts of cheap debt, neither reduced availability of loans nor a sustained increase in their cost is a welcome prospect. A recession would surely follow and downturn reduced corporate and consumer cashflows, as well as make it harder to meet interest payments and repay loans.

“This is why central banks may find themselves resorting to rate cuts and Quantitative Easing (and taking their chances with inflation as the lesser of the evils on offer).

- Rate cuts would lessen the appeal of government bond yields relative to cash on deposit and persuade savers to leave their cash in the bank, boosting banks’ capacity to lend and – in theory – make it more attractive for consumers and corporations to borrow.

- Rate cuts would also drag down the yield on government bonds and boost their prices. This would help the value of assets on banks’ balance sheets, boosting banks’ capacity and willingness to lend and – again, in theory – make it more attractive for consumers and corporations to borrow.

- Quantitative Easing would create a natural buyer for government bonds (and potentially corporate paper) in the form of central banks. As before, the goal of this buying would be to drive prices up and yields down on government issue, to make debt cheaper and tempt borrowers to borrow and use that credit to invest in their businesses and spend. Bond buying would also provide commercial banks with cash and liquidity, if it were needed.

“This is all straight out of the post-Great Financial Crisis playbook, and the EU could revive schemes such as the Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs) which provided cheap funding to banks in the economic bloc.

“Policymakers will be hoping that none of this is needed, and that existing insurance schemes for depositors, additional liquidity guarantees for banks and UBS’ takeover of Credit Suisse will stop the rot.

“Ultimately these interventions should be adequate, at least in Europe, where banks have shrunk their balance sheets and taken less risk and are better capitalised, more tightly regulated and subjected to fiercer stress tests than most of their US counterparts, where the banks with less than $250 billion in assets have taken a lot of risk, have grown their asset bases and freely (over)distributed capital to their investors via dividends and buybacks – even the US megabanks canned their buyback programmes in the second half of 2022 when they realised the error of their ways.

“Investors may have three guides to help them judge whether recession, more wobbles and a return to looser monetary policy (and even more money printing) is on the way, or whether the latest regulatory and central bank response is enough to stem the panic. They are:

- the yield curve

- the yield on two-year government debt (on both sides of the Atlantic)

- and the gold price (and some would add Bitcoin to that)

Yield curve

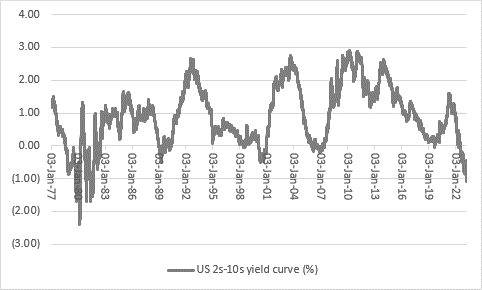

“Usually, ten-year government debt offers a premium yield relative to two-year paper to compensate holders for the risks presented by the extra timespan, and therefore the greater chance for something going wrong (inflation, interest rate changes or even default, in extreme cases). But sometimes ten-year paper offers a lower yield than two-year paper and this is seen as a recession signal, because it means markets are pricing in future interest rate cuts in response to the expected downturn.

“Until a week ago, the 2s-10s yield curve on US Treasuries was at its most inverted – two-year paper yielding more than ten-year – since the double-dip recession of the early 1980s. It is still inverted now and therefore bond markets are gearing themselves for a downturn, it seems. If they are right, that could prompt central banks to stop tightening policy and start loosening it if they fail to convince markets that they have the right tools for both economic stability and financial market stability.

Source: Refinitiv data

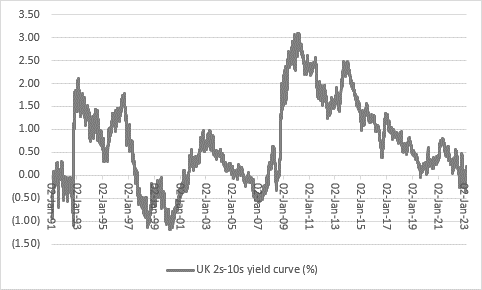

“In the UK, the 2s-10s yield curve on gilts is almost flat, after brief periods of inversion in autumn 2022 and then January and February 2023.”

Source: Refinitiv data

Two-year government debt

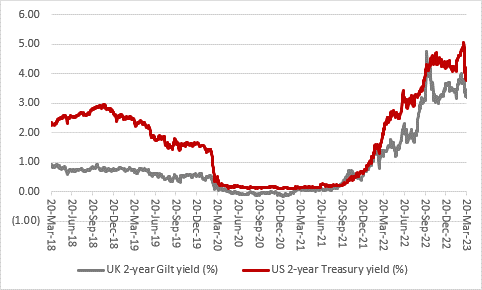

“Following the yield on just two-year government debt can be useful in another way.

“Usually, the yield on the two-year gilt in the UK and the two-year Treasury in the USA has moved six to nine months before the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve.

“Right now, the UK two-year yield is 3.21% (compared to a Base Rate of 4%) and the two-year Treasury is 3.76% (compared to a Fed Funds rate of 4.75%).

“If yields go lower, then the market is saying a recession is coming and policy is already too tight, although yields are likely to be volatile as markets second-guess central bank policy. A further complication is the reported closure of an Asia-based hedge fund that was expecting sharp interest rate hikes and was shorting US Treasuries (and betting on their yields to rise and price to fall), only for yield to fall and prices to rise as investors sought safety and began to ponder a pause or pivot in Fed rate policy. That could have forced the hedge fund to buy bonds to cover its positions and limit its losses, further boosting prices and reducing yields.”

Source: Refinitiv data

Gold

“Gold is pushing toward $2,000 an ounce once more.

“It is seen as a hedge against inflation (because it did so well in the 1970s when inflation roared) but really it is a hedge against policy error and central banks (and governments) losing control.

“That is why it did so well in the 1970s and again in the early 2000s.

“If gold breaks above $2,000 an ounce and motors on, we may indeed be getting a big policy pivot, but not because inflation is cooling but because the economy is slumping and central banks have unwittingly overtightened. A pivot to cutting rates (and possibly even a relaunch of Quantitative Easing) could be seen as an admission of policy error and that trouble lies ahead.

“A weak gold price, by contrast, could imply all is indeed still in hand, or that further policy solutions are at hand. One conceivable response to Senator Elizabeth Warren’s call for the insurance limit for US bank depositors to be increased could be to scrap the limit and switch to central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which would all come with the implicit backing of the local central bank.”

Source: Refinitiv data

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Wed, 01/05/2024 - 18:32

- Wed, 24/04/2024 - 10:37

- Thu, 18/04/2024 - 12:13

- Thu, 11/04/2024 - 15:01

- Wed, 03/04/2024 - 10:06