Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

The FTSE All-Share Banks sector is down by 43% over the past year and it will be uncomfortable for holders of Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, RBS and Standard Chartered (as well as the challenger banks) to learn that this is some way worse than the 35% fall seen across the sector globally over the same time period. Just when it seemed their profits would finally be free of PPI compensation claims and other (self-inflicted) legal and compensation costs, the banks must now assess the economic damage caused by the COVID-19 crisis and the quality of their loan books when they report their first-quarter results next week. A potential spike in provisions for sour loans could be the next hit to profit and loss accounts, which are still burdened by record-low interest rates and competition between lenders in mature, indebted markets which are crimping net interest margins.

Source: Refinitiv data

Consumers can now apply for payment holidays on their credit cards and mortgages, if their incomes have been affected by the outbreak, while the Government is clearly looking to banks to lend to see companies and individuals through the crisis, or at least roll over existing loans rather than calling them in. All of this exposes the banks to the risk of increase losses on their lending at a time of great economic uncertainty – although whether there is any great sympathy here from the public remains debatable, even if neither Barclays, HSBC nor Standard Chartered tapped taxpayers for bail-out cash over a decade ago.

Although different business mixes, geographic exposures and accounting standards mean it would be unwise to extrapolate too directly, the experiences of the big four Main Street banks in the USA – Bank of America, Citigroup, JP Morgan and Wells Fargo – may give some hint of what it is to come.

In the first quarter of 2020, the quartet set aside $24 billion to cover provisions on bad loans and potential future credit losses. That was the highest figure since Q1 2010’s $30.8 billion, when America was, like the rest of the world, staggering out of the recession that accompanied the Great Financial Crisis.

US bank bad loan provisions by quarter, Q1 2006 to Q1 2020

Source: Company accounts. Figures in $ million.

The four Main Street US banks took total loan book losses of $87 billion in 2010, a figure only beaten by 2008 and 2009 century. The decision to book $24 billion in Q1 alone gives some indication of how tough the big four think times could get, although a new accounting wrinkle, released in 2016 and enforced in 2020, means that the lenders now have to book a loss as soon as they think they may suffer one, rather than wait for a missed interest payment. This regime, known as ‘current expected credit losses’ could have conceivably brought forward the booking of losses and in a best-case scenario mean that the US banks have over-provisioned, in the event the American economy enjoys a V- or even U-shaped recovery in the second half of 2020.

US bank bad loan provisions by year, 2000 to Q1 2020

Source: Company accounts. Figures in $ million.

The highest combined quarterly loan loss provision and asset impairment hit taken by the Big Five FTSE 100 banks this decade was the £11.6bn aggregate charge swallowed in Q2 2010 as the effects of the Great Financial Crisis continued to reverberate.

FTSE 100 banks’ bad loan and asset impairment provisions by quarter, Q1 2010 to Q4 2019

Source: Company accounts. Figures in £ millions. HSBC Q4 2019 figure excludes $7.349 billion goodwill impairment.

Interpreting the American figures on a literal basis, investors could be forgiven for fearing for a return to that sort of level in Q1 2020. However, the Prudential Regulatory Authority has tried to cut the Big Five FTSE 100 banks some slack with its guidance in March that there is no immediate requirement to treat coronavirus-impacted loans as impaired assets under the IFRS9 accounting standard which was applied in 2018.

This may provide the quintet with some valuable breathing room and stave off a return to the sort of overall loan and asset impairment charges of 2010, which came to £37.6 billion, way higher than the £7.7 billion booked in 2019. However, loan and asset charges had already begun to creep higher, having hit bottom in Q1 2018, to suggest the global economy had already been showing signs of stress before the crisis provoked by COVID-19.

FTSE 100 banks’ bad loan and asset impairment provisions by year, 2001 to 2019

Source: Company accounts. Figures in £ millions. HSBC Q4 2019 figure excludes $7.349 billion goodwill impairment.

Besides the size of any loan provisions, analysts and shareholders will look to deposit and loan growth as they try to judge how the viral outbreak is affecting the banks’ customers and the wider economy. In the US, there was a clear dash for cash as deposit growth easily outstripped loan growth in the first quarter:

| Deposits | Loans | |

|---|---|---|

| JP Morgan | 23% | 6% |

| Bank of America | 15% | 11% |

| Citigroup | 15% | 6% |

| Wells Fargo | 6% | 2% |

Source: Company accounts

The UK banks had begun to show some loan book growth before the crisis so it will be interesting to see how quickly customers began to pull in their horns.

Year-on-year loan growth

| Q1 2018 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 2019 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barclays | (16.5%) | (17.7%) | (14.2%) | (10.7%) | 1.3% | 5.7% | 4.9% | 3.9% |

| HSBC | 12.0% | 5.8% | 3.8% | 1.9% | 2.5% | 5.0% | 3.7% | 5.6% |

| Lloyds | 0.0% | (2.4%) | (2.2%) | (2.6%) | (0.9%) | (0.2%) | 0.4% | (0.9%) |

| RBS | (2.3%) | (1.9%) | (1.6%) | (5.6%) | (4.0%) | (2.9%) | (0.0%) | 7.1% |

| Standard Chartered | 9.1% | (5.1%) | (9.4%) | (10.2%) | (9.9%) | 3.3% | 7.4% | 4.7% |

| Total | (3.8%) | (3.4%) | (1.7%) | (1.0%) | 2.7% | 4.3% | 5.8% | 2.1% |

Source: Company accounts

After loan provisions, lending growth (and any possible restructuring and conduct costs) the next key factor to shape the profit and loss account of the banks will be their net interest margins. They have been under pressure for some time.

| Q1 2018 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 2019 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barclays | 3.27% | 3.22% | 3.22% | 3.20% | 3.18% | 3.05% | 3.10% | 3.03% |

| HSBC | 1.67% | 1.66% | 1.67% | 1.66% | 1.59% | 1.61% | 1.59% | 1.58% |

| Lloyds | 2.93% | 2.93% | 2.93% | 2.93% | 2.91% | 2.89% | 2.88% | 2.88% |

| RBS | 2.04% | 2.01% | 2.04% | 1.95% | 1.89% | 2.02% | 1.97% | 1.93% |

| Standard Chartered | 1.59% | 1.59% | 1.56% | 1.57% | 1.56% | 1.62% | 1.56% | 1.54% |

Source: Company accounts

This combination of factors will then shape the headline pre-tax profit figures. In Q1 2019, the Big Five FTSE 100 banks racked up an aggregate pre-tax profit figure of £9.8 billion, their best result since Q1 2013, although performance tailed off in the second half, thanks to a final rash of PPI costs and an increase in loan losses, amongst other things:

FTSE 100 banks’ stated pre-tax income by quarter, Q1 2013 to Q4 2019

Source: Company accounts. Figures in £ million.

Usually investors’ attention would then switch from the banks’ profit and loss accounts to their cash flows and dividends. But not this time. The Prudential Regulatory Authority has leaned on the Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, RBS and Standard Chartered to cancel any share buyback programmes and withhold dividend payments.

This prompted the quintet to cancel some £7.5 billion in final dividend payments for 2019 and to declare that they will make no distributions in calendar 2020. Before the crisis struck, analysts had been expecting the banks to offer regular and special dividends worth some £15.5 billion in 2020.

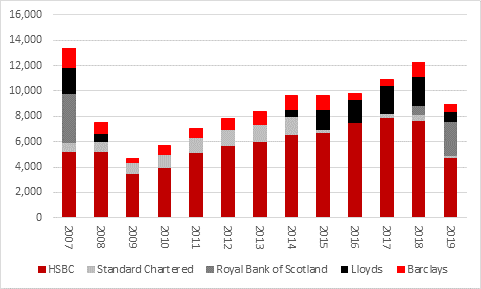

FTSE 100 banks’ annual dividend payments, 2007 to 2019

Source: Company accounts. Figures in £ millions.

It remains to be seen whether the banks feel able, from a financial, regulatory or political perspective, to declare a final dividend alongside their 2020 full-year results in early 2021 and make those payments in the spring next year, bringing succour to income-starved investors. The current consensus forecasts from analysts suggests that might be the case, although heavy loan losses over the course of 2020 could force the banks to hold off and even admit that the PRA was right in asking them to keep more capital on their balance sheets so they could absorb any such hit.

The loss of the dividend yield removes a big part of the investment case for holding banking shares, especially as they were unlikely to generate substantial earnings growth before the viral outbreak, given how they operate in mature, regulated, competitive and already highly-indebted markets. The only way to crank up growth would have been to crank up risk, either via leverage or the loan book or via investment banking operations and it is unlikely that shareholders, regulators, politicians or the public would have thanked them for that anyway, given the likely consequences.

As a result, the banks’ real attraction now is their valuation, as all of the Big Five trade at a discount to their last stated net asset, or book, value per share figure.

Source: Company accounts, Refinitiv data

That partly reflects markets’ concerns over how loan losses could eat into balance sheets but it also implies that investors have real doubts as to whether banks’ return on equity will ever consistently exceeds their cost of capital. This is understandable in zero interest rate world where regulators are dictating who can pay dividends, customers are being given interest payment holidays, the IMF is recommending debt forgiveness for emerging markets and Governments are urging them to offer cheap loans to keep the economy going. Investors in banks can only hope that this is a passing phase owing to the extraordinary circumstances posed by the crisis and that it will pass relatively swiftly.

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Wed, 17/04/2024 - 09:52

- Tue, 30/01/2024 - 15:38

- Thu, 11/01/2024 - 14:26

- Thu, 04/01/2024 - 15:13