Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

There are so many more important things to consider than financial markets when a war breaks out, but central bankers, economists and investors could be forgiven for keeping an eye on the oil price in particular, while they hope for a speedy and peaceful resolution to the conflict between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

There have been numerous outbreaks of armed conflict since 1945 and few have had a lasting impact upon share prices, with 1973’s Yom Kippur War the major exception. That led to the 1973-74 Oil Price Shock and in turn fuelled inflation and forced dramatic interest rate increases in the US and UK, so from the very narrow perspective of investment a repeat of that would be particularly unwelcome.

| FTSE All-Share | S&P 500 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict | Date | 1 year before | 1 year after | 1 year before | 1 year after | |

| Six Days War, Middle East | 05-Oct-67 | 23.20% | 40.20% | 29.40% | 7.30% | |

| Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia | 20-Aug-68 | 54.10% | (16.60%) | 4.40% | (3.90%) | |

| Yom Kippur War, Middle East | 06-Oct-73 | (11.90%) | (58.00%) | 0.00% | (41.20%) | |

| Russian invasion of Afghanistan | 24-Dec-79 | 3.10% | 25.50% | 11.80% | 26.20% | |

| Falklands War | 02-Apr-82 | 4.00% | 25.00% | (15.60%) | 32.90% | |

| Gulf War | 02-Aug-90 | (3.60%) | 9.40% | 2.10% | 10.20% | |

| Terrorist attacks on USA | 11-Sep-01 | -27.00% | (12.10%) | (26.60%) | (16.80%) | |

| Second Gulf War | 19-Mar-03 | (29.90%) | 22.50% | (25.30%) | 27.00% | |

| Gaza War | 08-Jul-14 | 5.20% | (1.50%) | 19.70% | 4.20% | |

| Russian invasion of Ukraine | 24-Feb-22 | 5.80% | 7.10% | 9.30% | (7.40%) | |

| Average | 2.30% | 4.20% | 0.90% | 3.80% | ||

Source: Refinitiv data

The duration and extent of the fighting in Gaza will therefore be important for many reasons, humanitarian and financial. If no-one else joins in and a speedy resolution is found then markets may breathe more easily, on so many levels. A swift peace could then even play to the investment strategy allegedly outlined by Baron Nathan Meyer Rothschild during the Napoleonic wars (and he denied ever saying it), that investors should, ‘Buy on the sound of cannons and sell on the sound of trumpets,’ although so far there has been little dip to buy.

The 2014 Gaza War lasted several weeks but it had no impact on oil prices, or therefore the global economy or financial markets. The fighting remained contained and no allies were dragged in to provide economic or military support of any scale. In fact, the price of oil tumbled in 2014, to a low of barely $45 a barrel from a peak of more than $100, as Saudi Arabia ramped up production in an attempt to restrict the growth of US shale oil and gas output.

Such considerations still pale relative to the human suffering caused by the wars, rebellions and insurgencies seen since 1945, especially as a brief look at the globe’s major conflicts since the institution of the UK’s FTSE All-Share in 1962 shows any negative impact upon stock markets tends to be relatively brief, even allowing for the effect of other events, such as shifts in policy, economic momentum and corporate profits.

Awful and frightening as all of those events were, American and British stocks have tended to show remarkable resilience on nearly every occasion.

One mild exception is 1968's Russian invasion of what was then Czechoslovakia to bring Alexander Dubček to heel, while the globe was already in the grip of a bear market before the terrorist attacks on the USA in 2001.

The greatest outlier, and thus biggest disrupter of financial markets, was 1973’s Yom Kippur War, when Israel fought off a joint attack launched by Egypt and Syria.

While the long-term effect of that conflict was a chain of events which led to the 1978 Camp David accords and 1979 peace settlement between Cairo and Jerusalem, the immediate consequence was OPEC’s oil embargo, imposed in anger at America’s support for Israel. Oil shot up from $4.50 to $14.50 a barrel when the Arab nations cut off supply of oil to Israel’s supporters, with the result that the price of crude shot up.

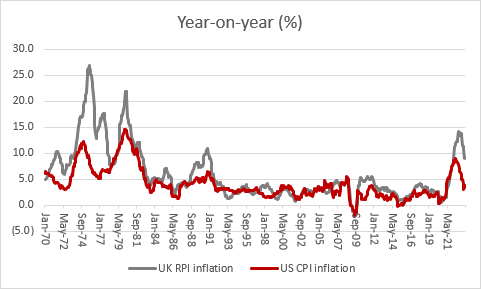

That in turn prompted a spike in inflation and higher interest rates and thus higher mortgage costs. The Bank of England did not control interest rates then, the Chancellor of the Exchequer did, and in response to higher energy costs and the wage price spirals that came next the incumbent at 11 Downing Street had to act: the Conservatives’ Tony Barber took the base rate to 13% in November 1973; Labour’s Denis Healey had to go to 15% in November 1976; and the Tories’ Geoffrey Howe surpassed both of those as he turned the screw all the way up to 17% in late 1979.

Source: Bank of England, US Federal Reserve, Refinitiv database

The US Federal Reserve also had to respond as it tried to rein in inflation. Chair Arthur Burns took the Fed Funds rate to 11% in 1974 and his successor Paul Volcker oversaw peaks of 16.5% in 1980 and then 19% in 1981 as inflation reached 15%.

Source: Office for National Statistics, FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve database, Refinitiv data. RPI used for RPI as offers a longer and more useful dataset

It is unlikely that the British or American economies would be able to stand such lofty borrowing costs as there is so much more debt in the system now than back in the 1970s and the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve could just find themselves stuck between the need to cut rates thanks to soaring government debts and interest bills on one side and the requirement to hold them firm on the other, thanks to inflation.

All asset classes – bar gold – took a pasting between late 1973 and early 1975 and the precious metal soared yet further after the second Oil Price Shock in 1979, which followed the Iranian Revolution and a reduction in supply of crude from Tehran.

It could also be argued the conflict which had truly lasting effects was Vietnam and that was perhaps because it lasted the longest of any of them. The 20-year war only ended when North Vietnam overran Saigon in 1975 and by then America had suffered dreadful casualties, pounding blows to its reputation as a global superpower and also great damage to its balance sheet. Perhaps it is therefore important from a selfish market perspective that the latest Middle Eastern conflict proves short and relatively contained, features which did not apply to Vietnam.

One of the reasons behind President Richard M. Nixon’s decision to take America off the gold standard in 1971 was its soaring debt burden, largely incurred owing to its military efforts in South-East Asia. The dollar lost around a third of its value across the rest of the decade and gold surged as the shift away from the Bretton Woods mechanism and toward floating currencies was swiftly followed by the oil shock, weak growth and uncomfortably high inflation.

There are therefore some potentially uncanny similarities between the 1970s and now, especially as government debt is soaring once more. Central banks are in danger of finding themselves between the rock of inflation on one side (which commands higher interest rates to quash it) and that of lofty debt on the other (which needs lower rates to ensure the interest bill is even vaguely manageable).

Source: FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve database

Stock and bond markets will therefore be pleased to see oil trading below $90 a barrel. If that remains the case, then the impact upon global markets and the global economy may be limited, for all of the harrowing nature of the pictures coming back from the Gaza Strip.

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Thu, 09/05/2024 - 08:44

- Mon, 29/04/2024 - 09:30

- Wed, 17/04/2024 - 09:52

- Tue, 30/01/2024 - 15:38