Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

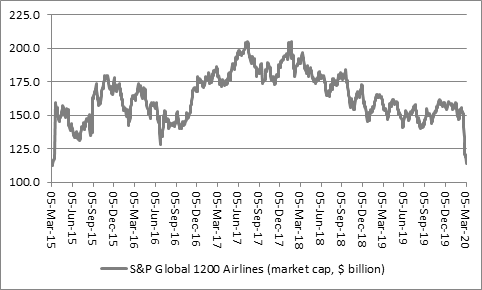

As investors try to work out what could be the short- and long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak upon the global economy, corporate profits and therefore share prices one sector in particular has taken a fearsome battering. The global airline sector’s market capitalisation has dropped by $40.6 billion, or 25%, in the last month alone. The sector’s valuation now stands at a five-year low and 45% below its January 2018 peak of $205 billion, as benchmarked by the S&P Global 1200 airlines index.

Source: Refinitiv data

This feels like a return to the bad old days, when airlines used to go bust at the drop of a hat and the industry attracted the ridicule of legendary investor Warren Buffett, rather than his support – three of the top 15 holdings in Berkshire Hathaway’s equity portfolio are now airline stocks, in the form of Delta, Southwest and United Continental.

It is also a massive contrast to just three years ago when Doug Parker, the chairman and CEO of American Airlines, went so far as to argue that the industry was indeed different this time as he commented: ‘I don’t think that we’re ever going to lose money again. We have an industry that’s going to be profitable in good times and bad.’

Such words came perilously close to saying ‘this time it’s different,’ a phrase described by Sir John Templeton as ‘the four most expensive words in the English language,’ and right now it looks like Sir John’s words are offering more protection to portfolio builders than those of Mr Parker.

Granted, the S&P Global 1200 airlines kept rising after Mr Parker’s bullish assessment – but only for three months. Since then, the airline industry has been troubled by overcapacity, as new entrants and established players alike have targeted a bigger slice of the perceived profit bonanza, bizarre weather patterns, sluggish economies and now the Coronavirus outbreak.

Even before COVID19 the industry had started to struggle, weighed down by its own optimistic capacity expansion and increased price competition. FlyBe’s collapse in the UK is just the latest in a long list of recent failures that also includes Thomas Cook and Monarch, as well as Denmark’s Primera, Cyprus’ Cobalt, France’s XL Airways and Aigle, Iceland’s Wow Air and Slovenia’s Adria. Alitalia and Air India remain in terrible trouble.

Yet the virus is making life that much harder for the airlines, as business travellers and consumers cancel bookings or decline to make new ones.

In the past week alone, Scandinavia’s SAS and Norwegian Air have withdrawn their earnings guidance for 2020, Southwest Airlines has acknowledged a big drop in bookings, UnitedContinental has cut domestic flight plans back by 10% and Eastern-Europe focused Wizz Air has noted a sharp drop in demand for air travel.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) is currently quantifying the potential hit to global passenger revenues at a drop of between 11% and 19% in 2020 (with falls in air freight and cargo coming on top).

Airlines – and their shareholders – will be hoping that these estimates prove to be a worst case, but the truth is no-one knows what the ultimate impact will be.

All shareholders can do is think back to Mr Parker’s optimism of 2017, which proved to be a rather helpful ‘sell’ signal, and the industry’s history. Just as with all deeply-cyclical, highly-capital intensive industries where a small change in revenues can mean a big change in profits, the most dangerous time to buy airlines is when everyone is making bumper profits, paying out dividends and adding capacity so they can keep cashing in on the good times.

By contrast, airline stocks are at their cheapest when they are losing money, dividends are being passed and capacity is being cut. This is when share prices tend to hit bottom as weak players fail, take out capacity and the survivors emerge from the downturn all the stronger and better placed to benefit from the next upturn.

Take easyJet’s history as an example. It has benefited from growth in global tourism, taken market share and developed strong streams of ancillary revenues since it listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2000. Revenues in the year to September 2019 were £5.9 billion and pre-tax profits £430 million compared to £264 million and £22 million in 2000.

Source: Company accounts. Year to 30 September.

But there were still notable downturns in profits in 2003 and 2008-09 and investors will note how profits peaked in 2015 and 2016-19 has seen a sustained slide in profits, despite further revenue growth.

Investors will also note how the best portfolio returns from easyJet stock would have been made by buying when profits were at rock bottom and recovering, not when they were setting new cyclical highs, perfectly backing up Research Affiliates’ Rob Arnott’s assertion that ‘Investing in what is comfortable is rarely profitable.’

Taking that maxim to the next level, the question that investors now need to be asking themselves is how bad does it get for the airlines and at what point is it so bad that it is time to buy?”

Source: Company accounts. Year to 30 September.

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Thu, 09/05/2024 - 08:44

- Mon, 29/04/2024 - 09:30

- Wed, 17/04/2024 - 09:52

- Tue, 30/01/2024 - 15:38