Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

What are shares and how do you make money from them?

Many first-time investors will start by building a basic portfolio from funds. The next step is to look at shares in individual companies.

Investing in shares (also known as stocks and equities) can be both an exciting and rewarding activity. However, before you take the plunge it is worth having a good understanding of the fundamentals behind shares and share ownership.

BECOMING A PART OWNER OF A BUSINESS

It is important to define just what a share is. This might seem almost simple but when most investing is done entirely online it is easy to just think of a share as a number on a screen which goes up or down depending on movements in the market.

A share is exactly what it says, ‘a share’ of a business. Being a long-term investor is not akin to gambling on short-term fluctuations in a share price. When you buy shares in a company you are becoming a part-owner of that business.

As a shareholder you can make your voice heard on many decisions it takes, such as voting on acquisitions, big fundraisings and director pay.

Each share represents a percentage of the company and you are effectively entitled to a share of the cash it generates in proportion to the number of shares you hold.

The company won’t simply pay out your share of that cash on a regular basis. Instead, you stand to make money if the value of your shares increases and potentially from receiving cash in the form of dividends, which we will now explain in more detail.

How does share ownership work?

A neat way of illustrating how share ownership works is to go back to its origins in London.

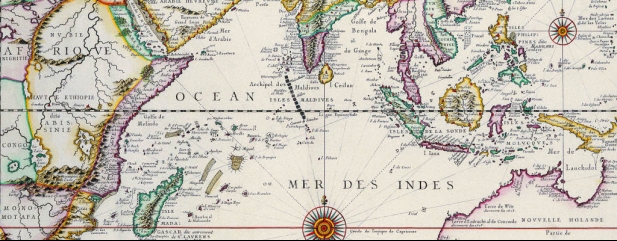

Trading of stocks and shares in the capital began in the 1680s with the need for money to finance two big voyages. These were the Muscovy Company’s attempt to reach China via the White Sea to the north of Russia and the East India Company’s push to explore India and the Far East.

Both journeys were set to be very expensive and neither could be funded privately. As a solution, independent merchants were asked to put up capital in return for a ‘share’ of any eventual windfall from these ventures.

Essentially a similar story is being played out in the 21st century with investors putting their money into businesses like BT (BT.A), Tesco (TSCO) and HSBC (HSBA) in order to gain access to their chosen company’s future profit and cash flow.

TWO TYPES OF RETURN

There are two ways of generating a return from an investment in shares. The first is the capital gain generated if the value of the shares increase, though this is only a ‘paper profit’ until it is crystallised by the shares being sold.

Shares typically go up (or down) based on supply and demand. If more people want to buy a share than sell it then the price will rise, if the reverse is true it will fall.

The other way of making money from shares is through dividends. These are typically paid twice a year but sometimes quarterly and they are funded by any cash generated by operations that a company has left over after shelling out for materials and services, paying its staff and investing in its business.

An example of how you might make money from shares

30-year old Mia works in product development for a large consumer goods company which unfortunately doesn’t offer its shares for trading on a stock market. Instead it is privately owned.

She is eager to use her knowledge of the industry to invest, and so she decides to buy shares in a rival business to her employer, being health and hygiene brands specialist Reckitt Benckiser (RB.).

She has £1,000 at her disposal which she invests on 1 April 2020. This buys her 16 shares at a price of £61.20, with approximately £20 left over which covers the cost of buying the shares (£10) and the rest put aside to go towards future investment account fees.

As she becomes a shareholder before the ex-dividend date, which is the

cut-off to be eligible for the next dividend, she is in line for the full year payment of 101.6p per share. For 16 shares this adds up to a dividend payment of £16.26.

By the time the dividend is paid on 28 May Reckitt shares have increased in value to £71.36. Mia’s 16 shares are now worth £1,141.76 compared with £979.20 she originally paid. Her total return including the dividend payment of £16.26 is 18.2% (£1,158.02 minus £979.20, divided by £979.20, multiplied by 100).

The combined contribution from capital gains and income is called the total return.

Not all companies pay dividends, but many do. According to data from SharePad, as at June 2020 around 52% of London-listed shares had paid a dividend in their previous financial year.

It is important to note that dividends are not guaranteed payments. They are paid at the discretion of the company and can be cut, suspended or cancelled altogether if management believe cash previously earmarked for dividends is better served by staying within the business or paying down debt.

In the next part of the series we will look at the wider stock market, how it works and how individual shares relate to it.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Feature

First-time Investor

Great Ideas

- Premier Foods is in a sweet spot as it breathes new life into the business

- Lam Research is a best in class stock you need to own

- Buy Touchstone now as it gears up for a big increase in production

- Microsoft shares hit new all-time high as it sees little coronavirus impact

- Fresh pork-to-poultry supplier Cranswick continues to sizzle

- Polar Capital’s shares are up 10% since we said to buy a week ago

magazine

magazine