Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Corporate debt crisis: The stocks you shouldn’t own

Coronavirus presents a big risk to corporate earnings if world trade is affected and companies’ supply chains are interrupted. While investors have begun to factor this risk into company valuations over the last month, when companies say they no longer have visibility over earnings it makes the job of valuing them a great deal harder.

Now, as the virus continues to spread, some investors are beginning to ask whether it could cause cash flow problems among businesses. Companies may find it hard to keep up debt repayments, potentially leading to collapse.

Just as coronavirus can kill people with health issues, it could potentially do the same to companies with underlying health problems.

To put it bluntly, you do not want to own any stocks at present which have very large debt positions relative to the value of their business and the scale of their earnings.

DAMAGE LIMITATION

Currently the number one priority for governments around the world is to try to stop the spread of coronavirus, for public health and economic reasons.

However, as events in China have shown, to really contain the spread of the virus entire populations have to be isolated for weeks at a time, and there is a heavy economic price to pay.

The ‘soft data’ from China in the form of industrial surveys has given us a taste of what is to come: the February manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI) collapsed to its lowest ever level, while new orders fell at the fastest rate on record.

Now some of the hard data is emerging: car sales in China, which is the world’s biggest market, tumbled by more than 80% last month due a combination of fewer vehicles being manufactured and a lack of buyers.

Analysts have rushed to downgrade their growth forecasts for the Chinese economy while at the same time pencilling in a sharp ‘V-shaped’ recovery later this year or early next year.

However, even if the Chinese economy does recover sharply, the rapid spread of coronavirus outside China is becoming a bigger threat to global growth.

RISKS MOUNTING

Without the political or logistical means to follow China’s example, countries around the world have adopted piecemeal strategies for containing the virus, with most asking the populace to ‘self-isolate’ rather than restricting movement.

Inevitably, these different approaches have met with differing results, and a view is forming among medical experts and politicians that rather than containing the spread of the virus the best they can now hope for is to delay its spread.

The director of the UK’s Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis has admitted that while the world ‘tried very hard to stop this virus, you can see from the statistics that the battle is really over’.

England’s chief medical officer has also said that an epidemic in the UK was now ‘highly likely’ and that the UK Government’s objective is now to mainly delay the spread of the virus.

The IMF has cut its fairly ambitious global growth target for this year from 3.8% to 2.9%, while the OECD has lowered its forecast from 2.9% to 2.5% and acknowledged that growth could be lower still.

In a worst-case scenario, the OECD has warned that several countries could be pushed into recession, meaning their economies contract, including Japan and countries in the euro area like Italy.

BEWARE OF GEARING

While markets have factored in a degree of risk from the spread of the virus, they still seem complacent about the potential long-term economic damage it could bring, especially in terms of company cash flows.

‘The speed of the market repricing has obviously been dramatic, however markets have only gone from pricing in no risk to a moderate risk,’ says Mike Riddell, manager of the Allianz Strategic Bond Fund (B06T936).

Dozens of companies in the UK and overseas have already warned of a downturn in revenues and a squeeze on earnings in the first two months of the year due to the spread of the virus.

The casualties haven’t just been manufacturing firms: a great many are service sector firms which are suffering from a drop in demand.

For firms which are operationally geared, meaning they have high fixed costs and need a certain level of income to generate profits, a fall in revenue is a major worry.

For firms which are not just operationally geared but also financially geared, meaning they have lots of debt which needs servicing, a fall in revenue could be catastrophic.

WHAT IS OPERATIONAL LEVERAGE?

When a company has low fixed costs relative to its revenues, for example items such as rent, utilities and general administrative expenses which are necessary for it to operate, it can be said to have low operational leverage. When a company’s fixed costs are high, it has high operational leverage.

While a company is growing, operational leverage is a good thing as an increase in revenues doesn’t cause an increase in fixed costs which means more of the income turns into profit.

A good example of a company with high operational leverage is Games Workshop (GAW). In its half-year results to 1 December 2019, revenue increased by 18.5% to £148.4m. However operating profit jumped by 37%, twice as much, to £48.5m. This was the result of operating expenses only increasing by 12%, allowing more of the increase in revenue to turn into profit.

Including royalties, which cost Games Workshop nothing to make and are therefore all profit, total operating profit grew an astounding 45%.

However, high operational leverage works in reverse too. Here, even a slight fall in revenue is magnified at the operating profit level. At the extreme a company may not generate enough cash to ‘cover’ its fixed costs, resulting in an operating loss.

WHAT IS FINANCIAL LEVERAGE?

When it comes to funding their business, companies have a choice. Traditional ways of raising money are to borrow from a bank or sell shares on the stock market, but today there are also plenty of ‘non-bank’ lenders prepared to offer money privately.

There are advantages and disadvantages to using debt. In legal terms, debt ranks higher than equity which means if things go wrong banks and bondholders can take over a company at the expense of shareholders. This can happen when financial covenants are breached, which was the case at retailer Debenhams, which is now owned by its lenders.

Covenants are designed to prevent companies from overstretching themselves financially and to protect debtholders. A typical requirement would be a ratio of net debt-to-earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) of less than four times.

Using debt responsibly can help companies pay lower taxes as interest payments reduce taxable profit, and can boost returns on equity. However too much debt can spell trouble for shareholders as their interests are put at risk from claims by lenders.

AA: The pains of financial leverage

Roadside assistance company AA (AA.) came to the stock market having been owned by private equity and ‘loaded up’ with borrowings. The company has struggled ever since to reduce its mountain of debt.

AA has a staggering £2.7bn of net debt while this year’s EBITDA is expected to be £347m according to data from Refinitiv, which gives the company a net debt-to-EBITDA ratio of 7.8 times. Any ratio above four times is considered a red flag for rating agencies and investors.

The firm’s financial leverage is so high that annual interest costs are equivalent to two thirds of operating profits, money that otherwise would end up in shareholder’s pockets.

BIG PROBLEMS AHEAD

In its latest global financial stability report the IMF ran a simulation which showed that in a recession only half as severe as the last crisis, companies with $19trn of outstanding debt would have insufficient profit to service their borrowings.

The collapse of UK airline Flybe is a textbook example of what can happen when a company which is operationally and financially geared suffers an unexpected drop in revenue.

Airlines have high fixed costs – for example leases on aircraft and staff costs – as well as large variable costs such as fuel.

They also tend to have high levels of debt, while all of their working capital comes from ticket sales. If the money from ticket sales falls – for example, because of an increase in competition or a fall in consumer confidence – they struggle to meet their operating and financial costs.

In the case of Flybe, which had been struggling financially for some time, a sudden drop in passengers due to fears over coronavirus proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

However it is unlikely to be the only loser in the sector. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has warned that coronavirus could cost the global airline industry over $110bn in lost revenue this year alone, more than three times the amount it estimated in February.

To put that in perspective, global airline industry revenues were $838bn last year according to the IATA.

Diamonds are not forever?

Shares in diamond producer Petra Diamonds (PDL) are sinking fast as it grapples with very high levels of debt and ongoing weakness in the diamond market.

Its latest half year results revealed a 6% drop in revenue to $194m, higher costs and a $37m jump in net debt to $596m. It has $650m of loan notes that mature in two years’ time. The market value of the business is now only £24m ($31m).

WILL RATE CUTS REALLY HELP?

Part of the reason for the complacency among investors is the feeling that, as in previous crises, central banks will have the markets’ back in terms of their ability to cut interest rates to stimulate demand and underpin share prices.

However, when the Federal Reserve Bank cut interest rates by 0.5% last week as a signal that it was ready to help indebted companies, US stocks actually went down.

This may have been the first sign that investors have started to realise that the damage to stocks may be greater than they first thought, and that rate cuts may not be the ‘silver bullet’.

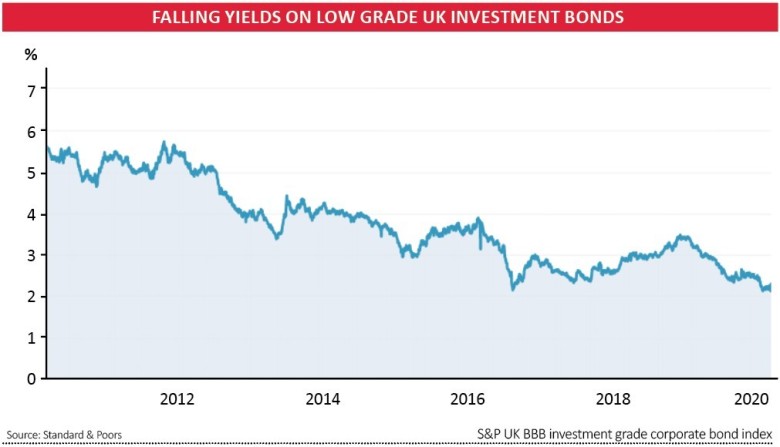

According to the OECD, global debt levels are at all-time highs relative to global output, and most of the debt issued by non-financial companies since the financial crisis has been low grade.

As David Jane, multi-asset fund manager at Premier Miton points out, ‘the problem with high debt levels is they reduce resilience to shocks, and what seemed sensible, even clever, when times were good can be terminal in the event of a shock’.

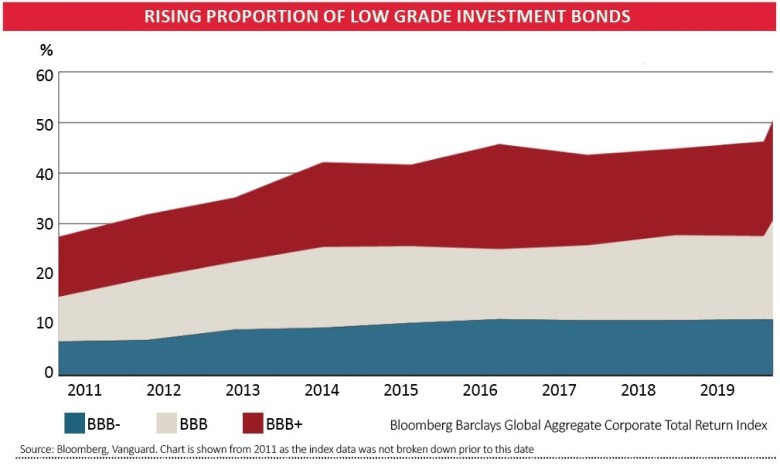

In the UK, the volume of low-grade corporate debt – rated BBB, the lowest level which still qualifies as investment grade – has ballooned since the crisis thanks to low interest rates and demand from bond fund managers for higher-yielding debt.

Analysts at asset managers BlackRock and Vanguard, and at UK bank Barclays, were voicing concerns late last year about the risks of the surge in BBB bond issuance.

Due to the size of the market and the fact that the balance sheet quality of many BBB-rated companies has deteriorated, the risk of defaults and downgrades is actually higher than at the start of the financial crisis.

Moreover, today’s stock of corporate debt has lower overall credit quality, longer maturities, worse protection for buyers – including the same ‘payment in kind’ clauses which were prevalent during the financial crisis – and higher payback requirements.

According to analysts at BlackRock, in the last three major downturns – 1989 to 1991, 2000 to 2003 and 2007 to 2009 – between 23% and 45% of investment-grade bonds were downgraded to junk.

‘If downgrade rates were to remain at such levels, the next downturn could see $600bn of BBB bonds consigned to junk status,’ they add.

WHO ARE THE BIGGEST BORROWERS?

In the UK, corporate net debt – that is total borrowings less cash – rose for the eighth year in a row to hit a record £443bn in 2019, almost 70% above the low in 2011 when UK companies were cutting debt after the financial crisis.

Most of the increase in UK corporate debt has happened in the last three years, with the oil sector seeing the fastest growth in net debt.

In 2018, oil majors BP (BP.) and Royal Dutch Shell (RDSB) accounted for an astonishing £1 in every £7 of UK plc’s net debt, according to Link Group’s Debt Monitor.

As the oil price collapsed in 2015, both firms undertook major restructurings and took on debt to help maintain their dividends while profits fell.

Another sector with high levels of net debt is consumer goods, with British American Tobacco (BATS) and Imperial Brands (IMB) accounting for three quarters of the total.

Further examples of consumer companies with high levels of net debt are Reckitt Benckiser (RB.) and Unilever (ULVR).

HERE’S THE TIPPING POINT

With supply chains disrupted and corporate earnings at risk if the spread of the virus is not checked, there is a danger that late payments to suppliers will push weak companies close to, if not into, insolvency.

Late payment has been described as the equivalent of ‘crack cocaine’ for large companies because many rely on it to finance their working capital without having to pay interest to banks or pay dividends to shareholders.

Therefore investors need to avoid companies that have weak cash flows, weak balance sheets, high levels of operational and financial gearing and ‘recovery’ or ‘special situations’ funds that invest in such companies.

WHO ELSE IS EXPOSED?

While most of the build-up in corporate debt has been outside the banking sector, there is no doubt that an increase in defaults would damage banks’ balance sheets, shrinking their capital.

At the same time, interest rate cuts by central banks will heap more pressure on net interest margins as it gives banks less room to eke out a profit on their lending.

Bond funds with a high proportion of BBB-rated or high-yield corporate debt could suffer if defaults and downgrades rise as a result of pressure on company profits.

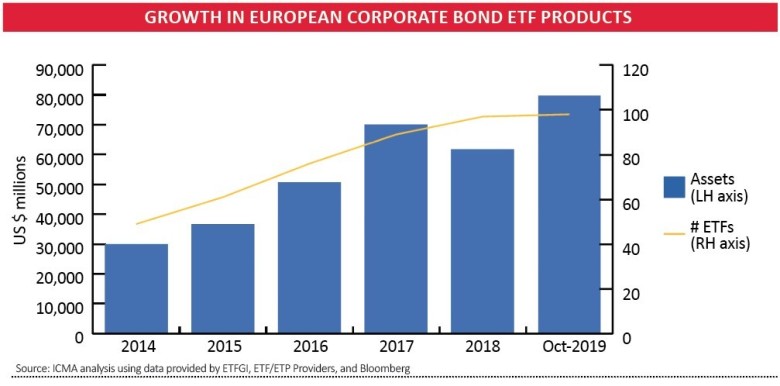

Investors also need to take care with European corporate bond ETFs which have grown to more than $100bn in value in the last five years. Funds with a high proportion of lower-grade bonds should be avoided.

Finally, investment trusts and funds with exposure to private debt and private equity may also be at risk depending on the quality of the assets and the level of protection assigned to the debt.

FIVE STOCKS YOU MUST NOT OWN

ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA

The case for not owning Aston Martin Lagonda (AML) shares seems fairly open and shut. Sales have gone into reverse, profits have vanished and now it is facing a major downturn in demand in China, one of its biggest markets, together with supply chain issues.

With falling revenue, the last thing the company needs is a pile of very expensive debt, yet net borrowing at the end of last year was £876m compared with a market value of £678m and forecast EBITDA this year of £223m, which is likely to be downgraded.

It has struck a deal to raise £500m of new money but that might not be enough if its problems get worse.

ROLLS-ROYCE

Aircraft engine maker Rolls-Royce (RR.) may not seem an obvious stock to avoid given that one day last month it was the only gainer in the FTSE 100, but the challenges facing it give us cause for concern in the present climate.

Problems with its Trent 1000 engine are well documented, leading to another £1.4bn exceptional charge in last year’s results and leading long-standing customers such as ANA to switch suppliers to rival Pratt & Whitney, depriving it of sales and lucrative after-market service revenue.

Less well documented is Rolls’ operating leverage – sales and operating costs eat up 95% of revenue, meaning a drop in turnover from customers switching or, say, its end-clients the airline operators cutting back on capacity, could wipe out earnings.

Meanwhile the company’s debt pile has increased due to new rules on lease accounting and there is £1bn of off-balance sheet financing in the form of ‘factoring facilities’ which it claims is standard.

Now feels like the wrong time to own such an operationally geared company.

GYM GROUP

The timing of the coronavirus outbreak was unfortunate for gym operators as it gives members a valid reason to quit the gym at the time of the year when operators typically sign up a large number of new members.

In addition, there is an increasing risk that businesses will temporarily close offices, requiring staff to work from home in an attempt to stop the spread of the virus. A fair number of gym goers will be lunchtime or after-work users of a gym near to the work place, potentially impacting membership.

Gym Group (GYM) has grown rapidly; opening 15 to 20 sites a year, and made some significant acquisitions, notably Lifestyle and EasyGym.

As a result, net debt-to-EBITDA has reached a high 4.7 times, although some of this debt is backed by a property portfolio. The business may be vulnerable to a sudden drop or slowdown in revenue growth. Debt interest consumes two thirds of operating profit.

CINEWORLD

Global cinema operator Cineworld (CINE) increased its already high financial leverage on the eve of the outbreak of the coronavirus. Shareholders approved the debt-financed $2.8bn (£1.6bn) takeover of Canada’s Cineplex on 11 February.

Buying Cineplex adds $2.3bn, or £1.7bn, of extra debt. That takes net debt to $5.6bn (approximately £4.19bn), tipping the gearing level to four times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA). Statistically, this level significantly increases the chances of default.

Management intends to reduce leverage towards three-times by 2021, but this ambition was articulated before the current epidemic appeared.

Cineworld was already weighed down by significant debt as a result of buying Regal Entertainment in the US. Adding even more debt with the Cineplex deal looked like madness, in our view. We’ve been long-term fans of the business but the latter acquisition was a tipping point and made the stock unappealing because of the debt. Now the coronavirus has made the situation even worse.

The company says it hasn’t seen evidence of admissions falling, but there is a risk that people become more circumspect about spending a couple of hours sitting next to complete strangers, when they can safely stream content directly into their homes.

Italy has closed its cinemas across the country in an attempt to curtail the spread of the virus, and the release of the new James Bond film has been postponed worldwide until much later this year which suggests that Hollywood is very nervous about cinema demand near-term.

People working from home and shunning leisure experiences aren’t going to go out twice as much once the coronavirus scare dies down. This is lost revenue for leisure companies which they won’t get back at a later date.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine