Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Will the global M&A love-in end in tears?

Readers may beg to differ but this column is pretty sure that it was the Financial Times newspaper’s Barry Riley, in his always-readable Long View piece, who coined the phrase ‘the urge to merge’ when it came to corporate merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. (If anyone disagrees and has proof to the contrary then please let me know).

Judging by statistics generated by Bloomberg that urge, as Riley decorously put it, seems to be burning strongly. In 2019, a record 32,344 M&A deals were struck worldwide, the fourth consecutive all-time high. Last year also witnessed a new peak in transaction values. Completed M&A activity reached $3.6tn, the sixth straight new all-time record.

This rash of activity is usually seen as a good thing for three reasons:

• Investors will welcome a bid for their holdings. An approach can be the ultimate justification of an investment thesis, as a company buys into their rationale for owning the shares to the ultimate extent of wanting to own them all, with the result that the investor books a healthy profit on their position (or in a worst case is at least spared further misery from one and can emerge with some dignity and money intact).

• While not all deals are paid for solely in cash, with stock frequently involved as an acquisition currency, M&A transactions can provide investors with fresh funds to put into the market, providing additional liquidity.

• Deals usually come at a healthy premium to the target’s share price. The valuation paid can potentially make other firms in the same sector or industry look cheap by comparison, stoking interest in them from either financial buyers (such as investors) or other corporations who may start to fear that they are missing out (and then themselves dive in with the next bid to keep the M&A action going).

However, not everyone may be caught up in the urge to merge. Experienced investors will note that global M&A activity peaked in 2000 and 2007, just as equity market bull runs peaked and then collapsed during the bear markets of 2000-03 and 2007-09. There was also a wobble in 2012-13 as the Greek debt crisis reached its zenith and confidence in the global economic outlook wobbled as Athens requested a bail-out.

Peaks and troughs

The same trend can be seen in those deals which involved just UK firms, which also hit a record high in 2019.

This may be why Riley referred to the ‘urge to merge,’ since it seems that cool and calculated thinking is not always evident when it comes to big M&A deals. After all, investors are taught that they should seek to buy low and sell high (if they feel they should sell at all), yet corporations appear most eager to get stuck into M&A deals when their targets’ share prices have already soared and they seem less willing to take the chance when share prices are depressed and there should be more value to be had.

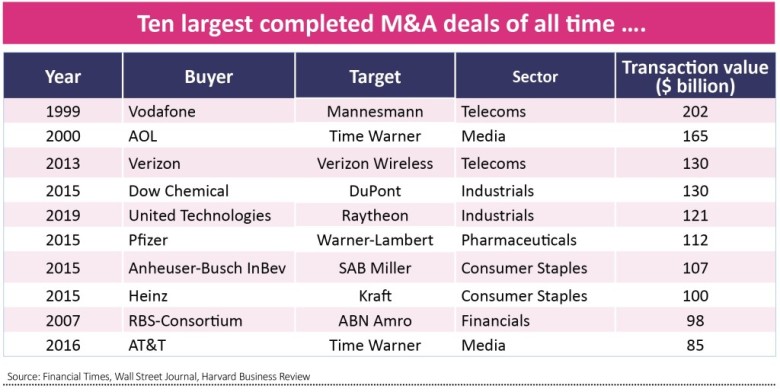

It is not just the sheer number of deals that picks up, either, as equity markets race higher. It appears that the size and scope of bids and mergers becomes more ambitious. But again, note how the biggest deals seem to come near market peaks. Even the $31bn bid from KKR for tobacco-to-food conglomerate RJR Nabisco, perhaps the first mega-deal involving private equity, was struck in 1989, just before a recession hit home and the US and global stock markets slumped.

Big disasters

Some investors may therefore view the latest M&A boom with a more jaundiced eye. Recessions and stock market accidents tend to follow M&A booms since ultimately someone, somewhere strikes a bad deal. Money and then confidence are lost with inevitable consequences.

Perhaps the best news about 2019’s M&A splurge, therefore, was that there was the absence of a new all-time high for the value of a single deal. This is because the track record of the very biggest deals is spotty. Vodafone (VOD) wrote down the value of German mobile telco Mannesmann by almost a quarter within six years, AOL and Time Warner demerged after 10 and the ABN Amro deal helped to bring Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) to its knees.

With the Financial Times reporting that January saw record issuance of both junk bonds and emerging market debt, and central banks keeping interest rates at rock bottom and markets nice and liquid, it seems likely that the M&A boom can run a bit further in 2020. But at some stage, there will come the deal that (with the benefit of hindsight) is seen as the one that broke the cycle, because of the price paid, the hubris involved or both, as per AOL-Time Warner and RBS-ABN Amro in the last two cycles.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine