Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Why markets may feel queasy when faced by a rising greenback

While UK-based investors will be well aware of how weak the pound is against the US dollar, languishing at a 14-month low around $1.28, sterling is not the only currency whose decline against the greenback is gathering pace.

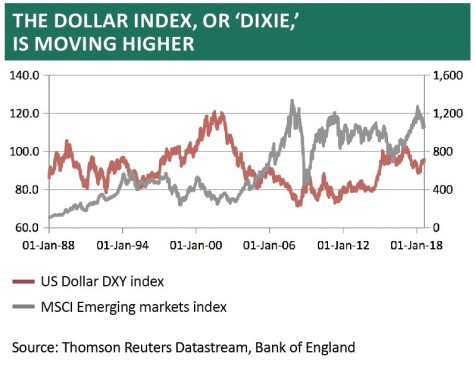

The DXY index, nicknamed ‘Dixie’ by foreign exchange traders, measures the value of the dollar against six major currencies. It stands at its highest level since June 2017 and investors need to keep a close eye on this situation.

Whether it is cause or effect may be a matter of debate. Yet periods of marked dollar strength have in the past seen chaos in emerging markets in particular – something which is relevant today with the Turkish crisis in mind – but also weakness in developed market stocks and commodity prices for good measure.

The big question now is whether the run in the DXY index – and thus the dollar against a basket comprising the euro, the yen, sterling, the Canadian dollar, Swedish krona and Swiss franc – is paving the way for a third major advance in the US currency since the so-called ‘Nixon shock’ and America’s withdrawal from the gold standard and Bretton Woods in 1971, following bull runs in the buck during 1971-1979 and 1985-1995.

GREENBACK GRINCH

If so, this is something investors would need to ponder for three reasons.

1. Emerging stock markets

These have been particularly sensitive in the past to the greenback, falling when the buck bounces and gaining when it rolls over. Dollar strength preceded the 1982 Mexican debt crisis, 1994’s

so-called ‘Tequila crisis’ (also in Mexico), the Asia and Russian debt and currency collapses of 1997-98, and also heralded a period of deep emerging market equity underperformance relative to developed arenas in the first half of this decade.

Emerging market investors run currency risk, as well as stock-specific risk. The old joke about emerging markets being called that because you cannot emerge from them unscathed when something goes wrong is unlikely to put too many smiles on faces right now.

Weakness in 2018 in the Argentine peso, South African rand, Russian rouble, Indonesia rupiah, the Mexican peso and Indian rupee can be explained away on a case-by-case basis, due to local political or economic developments, and the same applies to Turkey.

But concerns over current account or budget deficits (or both) and a reliance on overseas (dollar-priced) funding to some degree links all

of these currencies and Turkey’s particular mix of political and trade tensions with America leaves it right in the firing line.

The higher the dollar goes, the harder it is for these countries to fund their imports and pay interest on their dollar-priced debts, hitting growth and denting investor confidence in assets priced in their local currencies.

How serious the situation becomes will largely depend on the country’s economic policy response. Argentina is getting little thanks for the orthodoxy of its response, as the Macri administration turns to the International Monetary Fund and the peso continues to plunge, but Turkey’s refusal to raise interest rates and cut spending is putting even greater pressure on the lira.

According to data from the Bank of International Settlements, emerging markets represent one third of all non-bank borrowing outside the US that is priced in dollars, with liabilities of nearly $4 trillion.

It won’t take a big fall in their own currencies against the American one to make servicing those debts much more expensive, to the potential detriment of government and corporate cash flow, and thus economic growth, since interest payments will take precedence over investment (unless the borrowers decide to default or devalue or both).

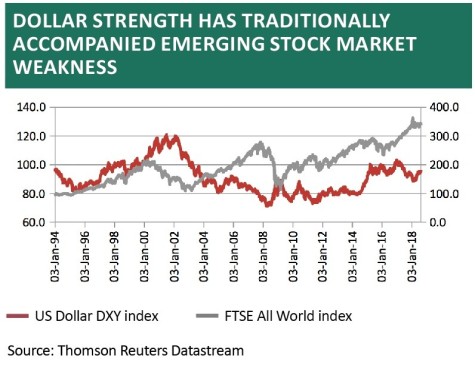

2. Developed stock markets and global risk appetite more generally may be affected

A dash out of emerging markets and into developed ones could also be a harbinger of a shift in risk appetite and this would be a marked change after a near-10 year bull run in almost any asset class you can think of (barring perhaps precious metals).

It is also worth noting that global stocks eventually came a cropper in 2000 after sustained dollar gains, thrived on the weakness of 2002-07 and then plunged again as the buck briefly soared in 2007-09.

All of this makes the broad stock market advances forged this decade appear like an interesting outlier, although a rising dollar did not immediately interfere with the bull market of the late 1990s.

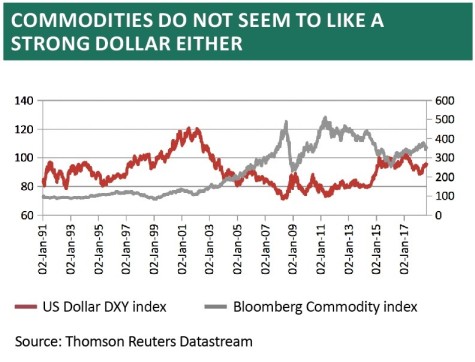

3. Commodities

These also have tended to do better during periods of dollar weakness and less well during periods of greenback gains. This is because most raw materials, with the exception of cocoa, are priced

in dollars.

If the dollar goes up then the product becomes more expensive to buy in local currency terms, potentially dampening demand.

In this context, summer’s weakness in copper and iron ore is eye-catching, as both can be seen as good proxies for global economic activity, due to copper’s use in cars, construction and a whole range of industries and iron ore’s importance in the steel-making process.

Russ Mould, Investment Director, AJ Bell

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Big News

- Hill & Smith directors take advantage of profit warning-led share weakness to snap up stock

- Investors shift focus to defensive stocks

- Pressure on corporate brokers implies potential wave of M&A

- Trump attacks the US Federal Reserve

- London hoteliers set to report bumper numbers following July heatwave

magazine

magazine