Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

“As a new trading week begins, the FTSE All-World index stands at a new all-time high, as does America’s S&P 500, while the FTSE 100 is holding firm above 7,000. All three benchmarks are being buoyed by vaccination programmes, fiscal stimulus from Government and ultra-loose monetary policy from central banks, a combination which is enabling markets to brush off the failure of the Archegos hedge fund as a little local difficulty rather than a warning of wider trouble ahead,” says AJ Bell Investment Director Russ Mould.

“Given the fire hose of fiscal and monetary liquidity in which they are bathing, markets may well be right. But investors thought the same in 2007 when two minor Bear Stearns funds failed after using considerable amounts of debt to goose their returns, on that occasion from sub-prime mortgages and derivatives thereof rather than US equities, as was the case at Archegos.

“Only time will tell whether the failure of Bill Hwang’s highly-leveraged fund is the first tinkling of a bell or not, but investors should at least consider Warren Buffett’s aphorism that speculation is most dangerous when it looks easiest.

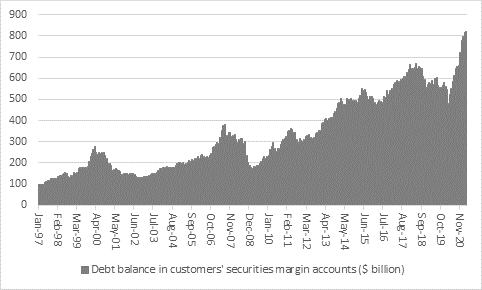

“And it does look terribly easy right now as headline share indices barrel higher. This may help to explain why US investors, professional and private, have borrowed record amounts with which to buy stock, according to data from US regulator FINRA.

Source: NYSE data to February 2010, FINRA data from February 2010

“It is tempting to dismiss this, by saying that the numbers are not as lofty when presented as a percentage of US GDP or market capitalisation.

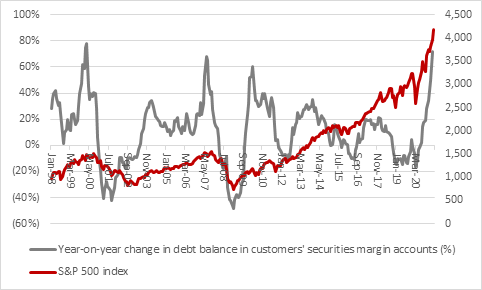

“But the 71% year-on-year growth rate is reminiscent of the market peaks in 2000 and 2007, to again show that risk-taking seems to be the order of the day. And it is that sort of risk-taking which makes market accidents worse as and when they happen.

Source: NYSE data to February 2010, FINRA data from February 2010, Refinitiv data

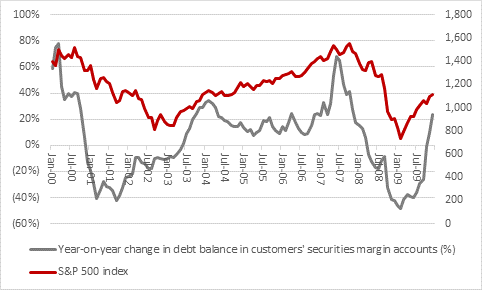

“Arguments that margin debt was not a concern owing to higher GDP or a larger economy saved no-one’s skin in 2007. Intriguingly, the year-on-year growth rate in margin debt in the USA peaked the very month in which those Bear Stearns funds went under, June 2007 and overall margin debt managed one more month of growth before it began to shrink.

Source: NYSE data to February 2010, FINRA data from February 2010

“This did not stop US equities in their tracks, at least not immediately. The S&P gained another 4-5% before it finally peaked in late autumn, but it was hard work as investors began to deliver, take less risk and liquidate holdings to ensure they repaid their borrowings in an orderly fashion.

Source: NYSE data to February 2010, FINRA data from February 2010, Refinitiv data

“That orderly liquidation helped to finally slow the S&P 500 down. Trouble begins when the sales are disorderly, as was the case in the select number of stocks owned by Archegos.

“There is no shortage of examples of what can go wrong when debt or complex trading strategies are deployed to try and gear up profits. They include Barings in 1995 ($1 billion loss), LTCM in 1998 ($3.7 billion) and Amaranth in 2006 ($6 billion).

“Even supposed ‘hedging strategies’, designed to dampen market risk have often only served to accentuate it. Examples here includes the ‘portfolio insurance’ programmes that contributed to the 1987 Crash, Metallgesellschaft losing its shirt in the oil market in 1992 and AIG’s significant contribution to the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09.

“In many ways, markets were overdue such an accident. The only question now is whether the damage is limited to the Archegos hedge fund, the US media and Chinese internet stocks which appear to have got it into trouble and those banks who acted as its prime broker, or whether there is a wider, spill-over effect.

“Such a knock-on effect can develop quickly. When an investment firm with lots of debt has large positions that are becoming stressed (and in the case of leveraged entities using margin, that can mean even small drops below the initial entry price), that institution may be forced to sell assets in order to meet margin calls and make good on its borrowing, according to the demands of its creditors. Such selling leads the market to drop further, which prompts further loss of value of the collateral, which forces yet more selling – and so on. This also means that assets classes entirely unrelated to the initial problem position(s) can be caught up in the melee – which explains the old market saying about how ‘all correlations go to one’ in a bear market, as distressed sellers just liquidate anything for which they can find a buyer.

“This is why Richard Bookstaber argues in his history of markets and hedge funds A Demon of Our Own Design that risk management models fail during crises, no matter how well designed they are. During a crisis, nothing else matters, other than who owns what, and who must sell even if they do not want to wish to do so.

“This is because any would-be seller has to find a buyer to take the paper off their hands.

History tells us this is not always as easy as it sounds, as J.K. Galbraith’s magisterial analysis The Great Crash shows. In his study of 1929’s market catastrophe he notes:

“Of all the mysteries of the stock exchange there is none so impenetrable as why there should be a buyer for everyone who seeks to sell. October 24, 1929 showed that what is mysterious is not inevitable. Often there were no buyers and only after wide vertical declines could anyone be induced to bid. Repeatedly and in many instances, there was a plethora of selling and no buyers at all.”

“Galbraith cites White Sewing Machine stock as an example. It plunged from $48 to $11 and yet no buyers emerged. Eventually an enormous block of stock was sold for one dollar a share.

“It is tempting to dismiss this as the follies of a distant era, of some 90 years ago and more. But FTSE 100 stocks were very hard to sell in size in 2008. There is every likelihood that the next market upset, if, as and when it comes, could see further distressed selling, not least because of those record margin positions, which smack of the sort of risk-taking which makes market accidents worse as and when they happen.

“The hard bit is no-one knows when that will be.

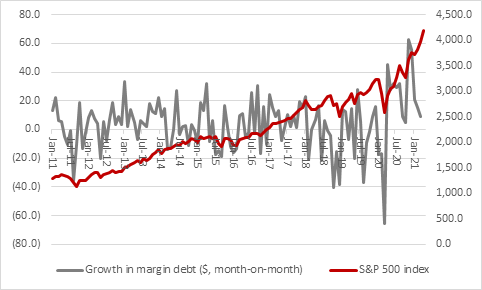

“One sign could be a slowdown in growth margin debt, or even a decline. The latest FINRA data, which cover March, show that margin debt grew by ‘only’ $8.9 billion from February, the slowest rate of increase since October. Further reductions in margin, voluntary or otherwise, might serve to rein in the seemingly rampant bull market, although Government and central bank largesse will surely have a large role to play, too.

Source: FINRA, Refinitiv data

“One person who learned the dangers of margin debt the hard way in 1929 was the comedian Groucho Marx. He bought stock on margin only to see prices collapse during the Crash and found himself a forced seller even at depressed prices so he could pay off his debts.

“Goldman Sachs stock was one of his biggest blunders – bought solely on the basis of a tip from his agent – though at least Marx was earning enough on stage and celluloid to keep him in wisecracks, noting after the Crash things were so bad ‘the pigeons started feeding the people in Central Park.’”

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Thu, 18/04/2024 - 12:13

- Thu, 11/04/2024 - 15:01

- Wed, 03/04/2024 - 10:06

- Tue, 26/03/2024 - 16:05

- Wed, 20/03/2024 - 16:30