Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

“While it seems unlikely that Edward Bramson and his Sherborne Investors vehicle will prevail in their campaign to get a board seat and reduce Barclays’ exposure to investment banking, the issues raised are not going to go away any time soon,” says Russ Mould, AJ Bell Investment Director.

“The debate over whether the investment bank adds value to the group’s customers and shareholders dates back to Barclays’ initial foray into the capital markets and the days of BZW in the mid-1980s and the operation must improve its financial performance if Jes Staley and the Barclays board are to move on.

“Mr Bramson’s argument that the investment bank soaks up too much of Barclays’ capital and provides too little return relative to that commitment is made clear by the 2018 annual report.

“Quite simply, the Corporate and Investment Bank business generates a return on tangible equity that is less than half that of either retail banking or the credit card and payments operation and soaks up nearly three-quarters as much capital as those two units combined.

| Group | Barclays UK | Barclays International | Head Office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return on tangible equity | 3.60% | 11.90% | 8.40% | Loss |

| Return on tangible equity excluding litigation and conduct costs | 8.50% | 16.70% | 8.70% | Loss |

| Average tangible equity | £44.1 bn | £10.0 billion | £31.0 billion | £3.1 billion |

| Corporate and Investment Bank | ||||

| Return on tangible equity | 6.90% | |||

| Return on tangible equity excluding litigation and conduct costs | 7.10% | |||

| Average tangible equity | £26.0 billion | |||

| Consumer, Cards and Payments | ||||

| Return on tangible equity | 16.50% | |||

| Return on tangible equity excluding litigation and conduct costs | 17.30% | |||

| Average tangible equity | £5.0 billion |

Source: Company accounts

“Mr Staley and his colleagues will point to reductions in this year’s bonus pool as a step in the right direction and the investment bank will have to do better if Barclays is to make its target of a 9% group-wide return on equity in 2019 and 10% in 2020, compared to last year’s 8.5% figure, once litigation costs and conduct fines are excluded.

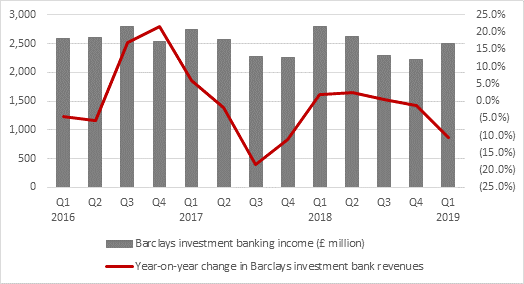

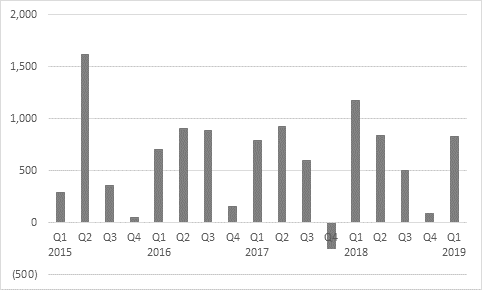

“How easy this will be remains to be seen. Even though we are in what appears to be a bull market in pretty much any financial asset that you can think of in 2019, investment banking revenues dropped 10% year-on-year in the first quarter, hampered by drops of 17%, 21% and 37% in banking fees, equities and corporate lending respectively.

Source: Company accounts

“Arguments that this was a better showing than those offered by the investment banking operations of UBS, for example, offer some succour, although those first-quarter numbers do make you wonder what would happen in a bear market. The slump in profits in the second half of 2018, as stock and bond markets wobbled, means this may not require too much imagination.

Source: Company accounts

“Moreover, there remains the danger that the investment banking model is in fact broken, thanks to changes in regulation and client and customer needs, with the result that historic returns could be difficult to achieve in the future.

“Investment banks no longer receive juicy commissions for dealing on behalf of their client, research has long since been disintermediated by fair disclosure valuations, with the result that its value has been reduced, and America’s Volcker Rule prohibits them from proprietary trading or investing in or owning a hedge fund or private equity fund (even if the subsequent Dodd-Frank legislation introduced some exemptions. Nor are clients particularly sticky, as there are still plenty of options available to them when it comes to choosing whose dealing, banking or advisory services to use.

“Leading shareholders and finance industry professionals – not to mention chief executive Jes Staley and the Barclays board – are clearly wedded to the concept of Barclays’ ongoing exposure to investment banking, given the kudos, growth potential and bonuses such operations can bring, so is seems unlikely that Mr Bramson will prevail in his campaign to rethink the operation’s role within the wider bank.

“A defeat for Mr Bramson will therefore doubtless be welcomed by most participants in the financial services industry.

“Nevertheless it would be interesting to see what response Barclays would get were it to ask its high street customers rather than its shareholders for their opinion. I suspect you might get a different perspective, with the memories of the crisis of a decade ago still fresh in the minds of savers and mortgage holders. Even allowing for the new ring-fencing requirements that came into force on 1 January 2019 there has to be a chance that many customers would feel Barclays would be better off with less exposure to investment banking, not more.

“And if Mr Bramson garners a sufficient percentage of the shareholder vote today, he may be encouraged to retain his investment in Barclays and keep up the pressure on Mr Staley and the board as any stumbles in the investment bank’s performance may provide Sherborne’s activist agenda with a more receptive audience next time around.”

The activist investor’s playbook

“Sherborne’s approach to Barclays looks to be a classic move from the activist’s playbook: find a share price that has done badly, where there is potential value to be unlocked – since Barclays’ shares trade at a one-third discount to the stated net asset value – and look for an angle that could improve operational performance to trigger that value release.

“In this case, Sherborne, under the guidance of Mr Bramson, is agitating for a reduction in Barclays’ exposure to investment banking. The unit’s financial performance can be volatile, its cost base heavy owing to the perceived need to retain rain-makers and talent and regulatory change is bringing long-term pressure to bear on the investment banking industry as a whole. To compound those issues, in Mr Bramson’s eyes, the corporate and investment bank works with some 60% of the total Barclays Group’s tangible equity, even though it provides returns which are much lower than those provided by retail banking and credit cards and payments.

“It is therefore possible to argue that a downsized investment bank offers less risk and more capital for the bank, which it can either investment in its other, more lucrative, operations or return to shareholders via dividends or share buybacks – and with the shares trading below NAV, calls for a buyback would be a common activist tactic.

Strategic options: spin or sell

- Asset disposals or spin-offs to recognise value

- Break-up

- Put the company in play for a bid

Financial options: more effective capital allocation

- Share buybacks

- Special dividends

- Dividend initiation or increases

Operational angles: improve performance

- Change the management

- Sale and leaseback of assets

- Close or restructure poorly performing units

Governance: improve reputation and lower risk

- Rein in excessive executive remuneration

- Ensure board has right balance, executive and non-executive

The case for shareholder activism

- Activists can unlock value for shareholders and improve corporate efficiency, boosting financial and operational performance to the benefit of management and stakeholders too. Calls for say a demerger, for example, can look opportunistic but if it means more capital is allocated to the core of the business and that core is run in a more focused way then it is the right thing to be doing.

- Activists do focus on governance issues such as executive pay and board composition, which are not always quick fixes. This can help to monitor and stamp out poor management behaviour and especially the curse of excessive boardroom pay.

- Activists are not always shouty or aggressive. Many prefer to be suggestivist and only go public if they feel they are not being given a fair hearing as a shareholder.

- They can get results. If a company’s shares have been underperforming for some time, it can be argued management should have already taken the initiative to resolve their charge's operational and share price woes before the activist's arrival on the scene

- An academic paper released in summer 2013 by Bebchuk, Brav and Jiang, entitled The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism asserted that target companies showed improved operational and share price performance for up to three years after an activist intervention.

- For example, Jeff Ubben’s ValueAct reportedly had a big hand in the removal of Steve Ballmer as the head of Microsoft in 2013 and under Satya Nadella the Seattle giant has successfully reinvented itself as a play on the cloud, via its Azure suite, and decreased its dependence on the PC, to the enormous benefit of profits, cashflow, the share price and therefore investors. Microsoft’s market capitalisation has just passed the $1 trillion mark for the first time.

The case against shareholder activism

This is not to say that everyone approves of Mr Bramson’s approach in this specific instance, or activist investors more generally.

Many executives, fund managers and commentators view activists as no more than Barbarians at the Gate to borrow the title of Bryan Burrough and John Helyar's 1989 book about the leveraged buy-out (LBO) of RJR Nabisco.

One particularly trenchant critic is Martin Lipton, a partner at US law firm Watchtell, Lipton, Rosen and Katz who has publicly attacked activists' lobbying tactics and even sued Carl Icahn and his firm Icahn Enterprises

Opponents of activism argue:

- It encourages a short-term approach which is not always to the benefit of the company.

- It can mean management kow-tows to a shareholder who, while important, will exert greater influence than those with larger stakes simply because they are making more noise.

- Activists can distract bosses from their job, namely running the company, and they can be tempted to start managing the share price rather than the assets. Some companies may be lured into offering a share buyback or a special dividend to goose a share price and appease an activist when that cash would be better used to invest in the underlying business and the long-term competitive position of the company rather than financial engineering.

On this point, Delaware’s chief justice, Leo Strine, argued in a 2014 issue of the Columbia Law Review [END] this year that a deluge of voting battles started by hedge funds only served to prevent management from doing their job properly.

- The activists are not always right. Bill Ackman of Pershing Square’s intervention in US retailer JC Penney was an outright disaster. In addition, the standard hedge fund ploy of returning cash to shareholders and even using debt to gear up the balance sheet and fund dividends would have destroyed many a firm in 2008 to 2009 as the credit crisis swept the globe and demand plunged across many industries.

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Wed, 24/04/2024 - 10:37

- Thu, 18/04/2024 - 12:13

- Thu, 11/04/2024 - 15:01

- Wed, 03/04/2024 - 10:06

- Tue, 26/03/2024 - 16:05