Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Sterling has suffered three crises of confidence since 1945, so a repeat cannot be entirely ruled out owing to the current political upheaval and lack of clarity on Brexit, although previous notable plunges have been the result of economic problems rather than any games of musical chairs at Westminster.

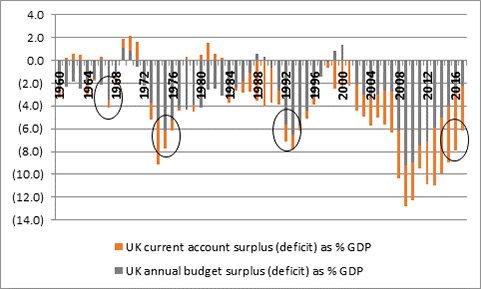

- Prime Minister Harold Wilson devalued the pound from $2.80 to $2.40 in 1967 as the UK struggled with a rising budget deficit, a trade deficit and a current account deficit, added to a weakening economy. The UK needed to attract capital to fund its triple deficits, or burn through its foreign exchange reserves, and Wilson chose a devaluation to limit national liabilities and lure investment into the UK from overseas.

- Sterling took a battering as then Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey had to turn to the International Monetary Fund for an emergency loan in 1976. Britain was struggling with weak growth, an inflation rate in the mid-teens and – once more – the combination of a growing budget deficit, trade deficit and thus current account deficit. Gilts were unattractive to buyers thanks to inflation and thus the Government turned to external help for near-term funding. Ironically, the IMF loan was paid back quickly as Treasury estimates for the 1976-77 budget deficit proved far too pessimistic.

- The currency was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism in September 1992 when in the care of the Conservative administration of John Major and Norman Lamont. The UK was mired in recession, burdened by what was seen as an uncompetitive, fixed rate relative to the German mark. The devaluation undid 1990’s move to join the ERM and demolished a key plank of the Major Government’s European policy.

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

There are potential similarities now:

- The UK is still running an uncomfortably high trade and current account deficit. Thankfully the annual budget deficit is coming down but Britain is still to a degree reliant upon the kindness of strangers to fund itself, to use Bank of England Governor Mark Carney’s words.

Source: ONS. Circles signify plunges in sterling (1967, 1975, 1992, 2016)

Thankfully there are differences, too

- There is no fixed exchange rate to defend, unlike 1967 and 1992, so the Bank of England does not have a big target on its back

- Interest rates are still near rock-bottom levels, so it easier for the UK to fund its borrowings

- The annual budget deficit has come down a lot over the past few years, even if Chancellor Hammond has pushed out plans to actually balance the budget to an unspecified date in the next decade

It is therefore hard to say that a new sterling crisis is inevitable although the pound does seem to trade as if it prefers a ‘soft’ Brexit to a ‘hard’ one and particularly to ‘no deal.’ Given the prevailing uncertainty in Westminster over the fate of the Prime Minister and the policy framework outlined at Chequers, the pound could remain under pressure.

The performance of the FTSE All-Share after those prior crises – and also after the EU referendum of 2016 - could offer some guidance as to what may happen in the event sterling comes under the cosh once more.

| Performance of FTSE All Share | ||||

| AFTER previous sterling crises | ||||

| 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| 19-Nov-67 | Sterling devalued | 1.80% | 15.60% | 31.70% |

| 28-Sep-76 | UK calls in IMF | 4.90% | 23.20% | 59.20% |

| 16-Sep-92 | Sterling exits ERM | 16.80% | 27.70% | 33.90% |

| 23-Jun-16 | EU referendum vote | 9.50% | 11.50% | 18.60% |

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

In the cases of 1967, 1976 and 1992, the market did well helped by falls in the pound and a lowering of interest rates, to the benefit of share prices.

In 2016 the FTSE All-Share initially tumbled upon news that Britain had voted to leave but then rallied as the heavyweight multinationals and overseas earners of the FTSE100 in particular dragged it higher – their foreign assets and income were instantly made more valuable once they were assessed in terms of pounds and pence, thanks to the pound’s post-vote plunge.

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice

Related content

- Wed, 17/04/2024 - 09:52

- Tue, 30/01/2024 - 15:38

- Thu, 11/01/2024 - 14:26

- Thu, 04/01/2024 - 15:13

- Fri, 17/11/2023 - 08:59