Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

The American politician John Connally packed a lot into his life, including a rare switch from the Democratic to the Republican Party, but he is best known for two things.

First, he was sat in the same limousine as John F. Kennedy when America’s thirty-fifth President was assassinated in Dealey Plaza, Dallas Texas in November 1963.

Second, as Treasury Secretary to President Richard M. Nixon, he oversaw America’s withdrawal from the Bretton Woods monetary system and the gold standard in 1971. This move reintroduced the concepts of floating currencies and paper money without any backing. It also led to an initial period of marked weakness in America’s currency, which prompted Connally to declare that “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem” as the US sought better trade terms and a lesser share of global defence and foreign aid expenditure.

Although the buck now trades much lower than it did in 1971 there have been three huge bear markets in the dollar since the so-called ‘Nixon shock’ (1971-1979, 1985-1995 and 2002-11) and three huge bull runs (1979-1985, 1995-2002 and 2011-2016).

Dollar has seen three big multi-year advances and three big multi-year drops since early 1970s

Source: Bank of England

This makes the latest period of dollar weakness particularly interesting, since the US currency is trading at three-year lows, even though the US Federal Reserve is tightening monetary policy much more assiduously than the Bank of England, European Central Bank or the Bank of Japan, and also looks likely to do more than any of its global counterparts in 2018.

Dollar has been weak despite tighter Fed policy

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

This has potential implications for investors’ portfolios, although basing asset allocations on the basis of currency movements alone is likely to be a mug’s game, given the unpredictable nature of the foreign exchange markets.

Dollar dive

Limited data availability is a bit of an obstacle but in general the following observations can be made, using a dollar index provided by the Bank of England (an alternative index for the dollar, known as DXY, or ‘Dixie’, can also be used and tracked quite easily):

- Real dollar strength has tended to coincide with times of uncertainty or even outright financial market stress (such as 2001-03, 2008-09 and even during this decade’s eurozone debt crisis).

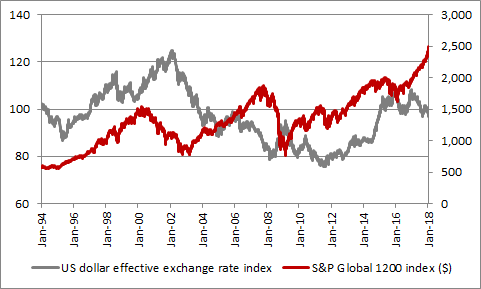

- Global stocks eventually came a cropper after a period of sustained dollar gains in 2000, thrived on the weakness of 2002-07 and then plunged again as the buck briefly soared in 2007-09. All of this makes advances forged this decade appear like an interesting outlier, although a rising dollar did not immediately interfere with the bull market of the late 1990s.

Global stocks have managed to shrug off dollar strength during this decade

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

- Emerging stock markets have been particularly sensitive in the past to the greenback, falling when the buck bounces and gaining when it rolls over. Dollar strength preceded the 1982 Mexican debt crisis, 1994’s so-called ‘Tequila crisis,’ also in Mexico, the Asia and Russian debt and currency collapses of 1997-98 and also heralded a period of deep Emerging Market (EM) equity underperformance relative to developed arenas in the first half of this decade. Recently EM fund managers have spent a lot of time convincing themselves and their customers that dollar strength is less of a problem now, as EM companies have a better balance between their assets and liabilities, but for the moment these finer points seem to be of less interest than before.

Emerging market equities have historically preferred a weaker dollar

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

- Commodities have tended to do better during periods of dollar weakness and less well during periods of greenback gains.

Commodities have historically preferred a weaker dollar

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

- Global government bonds have overall done best during times of dollar strength, as have global corporate bonds. Although the relationships are by no means clear-cut, this makes sense, if investors accept the thesis that a strong dollar heralds – or is symptomatic – of a ‘risk off’ period in markets, where dependable yields and capital safety are more likely to be highly prized. That said, Government bond yield are rising (and prices falling) as markets price in faster global growth and address the possibility that inflation may finally start to accelerate.

Government bonds appear to have done better during periods of dollar strength ...

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

... while a shorter index dataset suggests the same has been true for corporate, investment-grade bonds

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

- High-yield, sub-investment grade traded debt has apparently preferred a weaker buck. This intuitively seems sensible. High-yield debt tends to be riskier as the issuers tend to have weaker balance sheets. As such, an economic upturn (when havens such as the dollar are not in such great demand) should bring in welcome cash and make servicing debt easier, while a downturn (when havens are very much needed) will hit profits and make it harder to pay interest and return principal.

High-yield corporate bonds have tended to do best when the dollar has been weak

Source: Bank of England, Thomson Reuters Datastream

Conclusions

In all cases, it is hard to divine which is the chicken and which the egg with some of these trends and correlation is guarantee of causation. Other factors will clearly have been at work too.

However, currencies can be an interesting asset class to watch in the current environment, where central bank intervention in fixed-income markets mean that currencies rather than government bonds are the traders’ prime tool for expressing their views on a sovereign or its economic prospects.

In this context, some of the trends assessed above make sense.

A strong dollar is generally seen as deflationary because it makes dollar-priced commodities more expensive for non-dollar-based buyers, compressing their ability to spend elsewhere, and makes it more expensive for non-dollar nations and companies to service any debts they have that are denominated in the US currency.

Dollar weakness could also lift the US economy, as it gives exporters a competitive edge at a time when they are also basking in the glow created by tax cuts. This seems to be the stance taken by the current US Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, and it is one which fits with the Trump administration’s particular brand of economic nationalism.

America is the world’s biggest economy so faster growth may help lift other nations, providing some talking down of currencies does not lead to retaliation in the form of tariffs and protectionism. Dollar weakness may also ease fears of deflation.

It may therefore be that any sudden reversal in the dollar and renewed strength could be an early warning signal of wider trouble ahead, as investors decide they need to find shelter in a haven once more.

Russ Mould, AJ Bell Investment Director

Related content

- Wed, 17/04/2024 - 09:52

- Tue, 30/01/2024 - 15:38

- Thu, 11/01/2024 - 14:26

- Thu, 04/01/2024 - 15:13

- Fri, 17/11/2023 - 08:59