Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

At the start of 2017, India was the hottest topic in town when it came to Asian financial markets. Prime Minister Modi’s reform programme and falling interest rates were supposed to supplement helpful long-term demographics to provide strong corporate earnings and a soaring stock market.

For once, the consensus view was remarkably prescient. Mumbai’s SENSEX index surged to a new all-time high around the 32,500 mark in August.

India’s stock market has boomed in 2017

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

But the SENSEX has subsequently begun to paddle sideways, amid concerns over whether the launch of the new national Goods and Services Tax (GST) will lead to another blip in growth, to match that caused by 2016’s controversial decision to force citizens to exchange old 500 and 1000 rupee notes for newly-printed ones.

In addition, non-performing bank loans remain a potential encumbrance to the economy, earnings growth estimates for this year have slipped from 18% to 9% since January and their good run means India is no longer as cheap as it was. Research from Société Générale puts the market on a trailing price/earnings ratio of 22 times, a 16% premium to its ten-year history and a 40% premium to the wider Asia-Pacific region (compared to ten-year average premium of 33%).

India’s GDP growth has slowed in 2017 while China has confounded the bears and met expectations

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

By contrast, China has managed to meet its GDP growth targets, provide good earnings growth, glean additional exposure for domestic A shares in the MSCI regional benchmark indices and dangle the prospect of further reforms at the 19th five-yearly Party Congress which runs from 18th to 26th October.

As a result, China’s Shanghai Composite index is ending the year with a flurry, finally pulling clear of the 3,000 mark which has exerted a strong gravitational pull ever since the market’s mini-collapse of 2015.

In some ways, it should not be a surprise that China has met its growth targets. The Party’s legitimacy and credibility rest on growth, jobs and prosperity so a failure to meet its goals ahead of the Congress would have been too embarrassing.

All eyes are now on Beijing and the political and economic policy shifts that will take place in what should be a highly informative week. Providing President Xi Jinping can maintain control, markets could warm to the prospect of reforms and sustainable growth.

If his influence is diminished and Party apparatchiks establish a more committee-led leadership style, China could press the accelerator when it comes to fiscal stimulus and GDP growth. That could bring a near-term sugar rush but leave investors with a debt-fuelled hangover and greater risks further down the line.

Political priorities

The 63-year old Xi Jinping looks like a shoo-in for a second term as General Secretary of the Communist Party and President of the People’s Republic of China. The real interest may lie in who makes it onto the Politburo, as the majority of the 25-man body will be stepping down this time around, and particularly the seven-man Politburo Standing Committee, since five of its members are due to retire.

This reshuffle will open the way for others to step up and stake a claim for even higher office in 2022 – Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang both made it onto the Politburo Standing Committee back in 2007 on their route to the very top.

It will therefore be important to see who is promoted and whether they lean toward Xi’s market-pleasing agenda or not.

According to research from investment bank Société Générale, the key themes of the Congress are due to be:

- Reform of State-Owned Enterprises

- Improvements to the welfare state

- Controlling China’s burgeoning debts and a crackdown on shadow banking

The final point of the three could be the most contentious.

Second-quarter GDP rose CNY 7 trillion, year-on-year, but debt grew CNY 24 trillion so growth is being generated but at a potentially costly price further down the road, when those additional liabilities have to be met.

On the face of it, China’s sovereign liabilities are relatively modest at 46% of GDP.

But getting to the bottom of the numbers is difficult, as a lot of liabilities rest in the grey area that lies between the state and the private sector, in the form of the State-Owned Enterprises (SOE). Bank of International Settlements (BIS) estimates put the nation's total-debt-to-GDP figure at 255%, while McKinsey Global Institute analysis suggests China’s debts have quadrupled since 2007.

Given those numbers it may not surprise investors to learn that Standard & Poor’s cut China’s credit rating to A+ from AA- in September, following Moody’s move to A1 from Aa3 in May (the agency’s first downgrade of Chinese debt since 1989).

Old and new

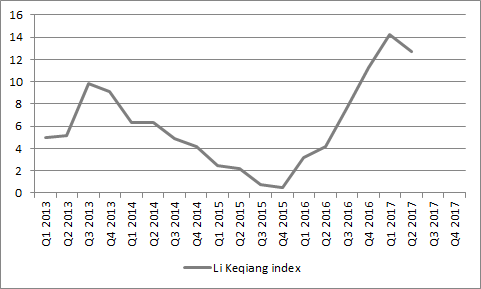

This is at least partly the result of the fiscal and monetary stimulus which China is using to keep growth on track and its implications can also be seen in the so-called Li Keqiang index. This is based on three indicators which the Prime Minister is believed to follow in preference to official Government growth statistics. This trio comprises:

- Demand for loans

- Rail cargo traffic

- Electricity consumption

The Li Keqiang index made a comeback in China in 2017

Source: Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters Datastream

With the rise of the Chinese middle class, increased consumption and the emergence of web-services giants such as Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba there was a gathering school of thought that the Li Keqiang index could be condemned to the dustbin of history. After all, it represents old, industrial China rather than the new, technology and e-commerce-led one. However, the readings improved (at least in early 2017) and this reliance on capital investment and exports rather than services and consumption suggests China has a long way to go before it rebalances its economy.

IMF growth forecasts for the Asian region in 2018

| GDP Growth | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 E | 2018 E |

| Australia | 2.4% | 2.7% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.2% | 2.9% |

| China | 7.7% | 7.4% | 6.9% | 6.7% | 6.8% | 6.5% |

| India | 4.4% | 7.2% | 7.3% | 6.8% | 6.7% | 7.4% |

| Korea | 2.8% | 3.3% | 2.6% | 2.8% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| New Zealand | 2.4% | 3.2% | 3.4% | 4.0% | 3.5% | 3.0% |

| Singapore | 4.1% | 2.9% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 2.5% | 2.6% |

| Taiwan | 2.1% | 3.7% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% | 1.9% |

| Emerging and Developing Asia | 6.5% | 6.8% | 6.6% | 6.4% | 6.5% | 6.5% |

| ASEAN-5 * | 5.2% | 4.6% | 4.7% | 4.9% | 5.2% | 5.2% |

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2017. * Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam

Stop-start progress

This explains why the Party Congress is so important. President Xi wants to keep cracking down on corruption and stop debt spiralling while keeping growth on track and the currency strong.

This is a difficult juggling act. Reducing debt could mean slower growth, albeit growth with more reliable long-term foundations.

If Xi’s influence is in any way diluted by the changed composition of the Politburo after the showpiece conference in Beijing there is a chance that the Party will embrace greater debts in exchange for faster growth in the short term and wobblier foundations in the long term.

All of this has potential implications for investors and not just those with exposure to Asian assets. China remains a growth engine for the world and its fortunes have implications for commodity demand and earnings growth the world over.

At least one pair of indicators is keeping the faith with the China story. Both can be easily followed by investors to help them judge whether the wheels are staying on the growth engine or not.

The first is the Shanghai Composite stock index, which is currently scorching higher.

The renminbi may be a good guide to China’s overall economic health

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

The second is the currency, the renminbi. The growth scares of summer 2015 and early 2016 both showed up first in weakness in the renminbi against the dollar. The more serene progress of 2017, aided and abetted by substantial stimulus ahead of the Party Congress, has seen the renminbi rally strongly, so any renewed bout of weakness could be an early warning sign.

Russ Mould, AJ Bell Investment Director

Related content

- Wed, 17/04/2024 - 09:52

- Tue, 30/01/2024 - 15:38

- Thu, 11/01/2024 - 14:26

- Thu, 04/01/2024 - 15:13

- Fri, 17/11/2023 - 08:59